Case Summary

| Citation | A. Raghavammav. A. Chenchamma(1964) 2 SCR 933 : AIR 1964 SC 136 |

| Keywords | Partition |

| Facts | There were 2 brothers B1 and B2, B2 died prior to B1 and B2’s wife is the plaintiff here and B1’s sole son died before B1, leaving his widow and a son. B1 died in 1945, leaving the minor as sole surviving coparcenor and that child died before reaching the age of majority. The widow of sole son of B1 is the defendant. Plaintiff contend that B1 executed a will in his grandchild’s name and she is entitled to get half portion as she was manager of the property. Defendant contend that as the minor was sole surviving coparcenor, so his portion will get to his mother, that is, defendant and existence of undivided coparcernor, B1 don’t have authority to make a will, and the will was void. |

| Issues | Whether partition can be done by simply declaring unequivocal desire to leave family without informing other coparcenor. |

| Contentions | |

| Law Points | The intention has to be declared and communicate to other coparcenors so that it comes to their knowledge about partition. The law is clear that if a coparcenor wants to separate, he has to declare his intention to others in clear and unambigous words. Severance is a mental state and statement is expression of that mental state and it does not arise from simple proclaimation. |

| Judgement | The intention of partition was not communicated to other coparcenor, so it does not result in severance in status. Before the testator dies, neither the minor nor his guardian was aware of the contents of the will, so it does not amount to partition. The property will go by survivorship. |

| Ratio Decidendi & Case Authority |

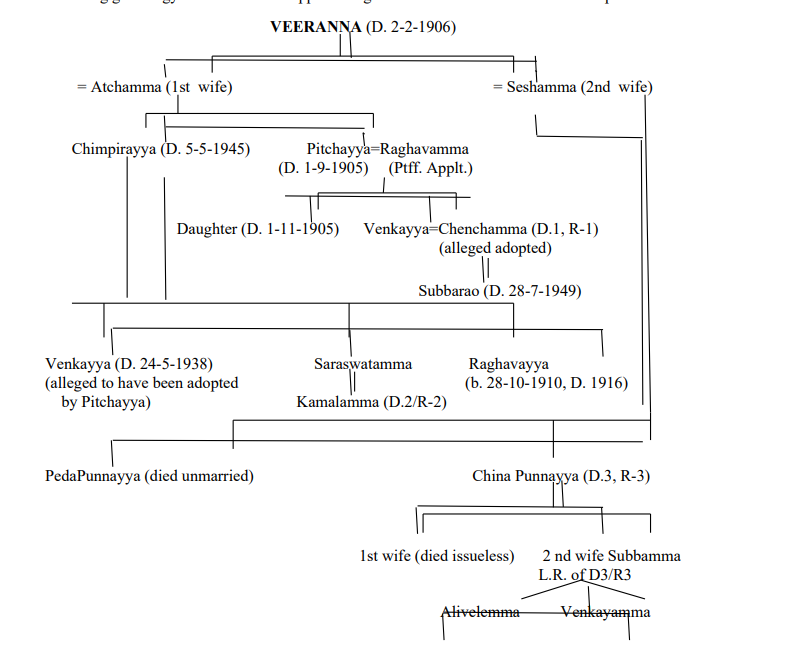

K. SUBBA RAO,J. – This appeal by certificate is preferred against the Judgement and Decree of

the High Court of Andhra Pradesh confirming those of the Subordinate Judge, Bapatla,

dismissing the suit filed by the appellants for possession of the plaint schedule properties. The

following genealogy will be useful in appreciating the facts and the contentions of the parties:

It will be seen from genealogy that Veeranna had two wives and that Chimpirayya and Pitchayya

were his sons by the first wife and PedaPunnayya and China Punnayya were his sons by the

second wife. Veeranna died in the year 1906 and his second son Pitchayya had predeceased him

on 1-9-1905 leaving his widow Raghavamma. It is alleged that sometime before his death,

Pitchayya took Venkayya, the son of his brother Chimpirayya in adoption; and it is also alleged

that in or about the year 1895, there was a partition of the joint family properties between

Veeranna and his four sons, Chimpirayya, Pitchayya, PedaPunnayya and China Punnayya,

Veeranna taking only 4 acres of land and the rest of the property being divided between the four

sons by metes and bounds. Venkayya died on May 24, 1938, leaving behind a son Subbarao.

Chimpirayya died on May 5, 1945 having executed a will dated January 14, 1945 whereunder he

gave his properties in equal shares to Subbarao and Kamalamma, the daughter of his predeceased daughter Saraswatamma; thereunder he also directed Raghavamma, the widow of his

brother Pitchayya, to take possession of the entire property belonging to him, to manage the same,

to spend the income therefrom at her discretion and to hand over the property to his two

grandchildren after they attained majority and if either or both of them died before attaining

majority, his or her share or the entire property, as the case may be would go to Raghevamma.

The point to be noticed is that his daughter-in-law, Chenchamma was excluded from management

as well as from inheritance after the death of Chimpirayya. But Raghavamma allowed

Chenchamma to manage the entire property and she accordingly came into possession of the

entire property after the death of Chimpirayya. Subbarao died on July 28, 1949. Raghavamma

filed a suit on October 12, 1950 in the Court of the Subordinate Judge, Bapatala, for possession of

the plaint scheduled properties; and to that suit, Chenchamma was made the first defendant;

Kamalamma the second defendant; and China Punnayya, the second son of Veeramma by his

second wife, the third defendant. The plaint consisted of A, B, C, D, D-1 and E schedules, which

are alleged to be the properties of Chimpirayya. Raghavamma claimed possession of A, B and C

scheduled properties from the 1st defendant, for partition and delivery of half share in the

properties covered by plaint-schedule D and D-1 which are alleged to belong to her and the 3rd

defendant in common and a fourth share in the property covered by plaint-schedule E which are

alleged to belong to her and the 1st and 3rd defendants in common. As Kamalamma was a minor

on the date of the suit, Raghavamma claimed possession of the said properties under the will –

half in her own right in respect of Subbarao’s share, as he died before attaining majority and the

other half in the right of Kamalamma, as by then she had not attained majority, she was entitled to

manage her share till she attained majority.

2. The first defendant denied that Venkayya was given in adoption to Pitchayya or that there

was a partition in the family of Veeranna in the manner claimed by the plaintiff. She averred that

Chimpirayya died undivided from his grandson Subbarao and, therefore, Subbarao became

entitled to all the properties of the joint family by right of survivorship. She did not admit that

Chimpirayya executed the will in a sound and disposing frame of mind. She also did not admit

the correctness of the schedules attached to the plaint. The second defendant filed a statement

98

supporting the plaintiff. The third defendant filed a statement denying the allegations in the plaint

and disputing the correctness of the extent of some of the items in the plaint schedules. He also

averred that some of the items belonged to him exclusively and that Chimpirayya had no right to

the same.

3. On the pleadings various issues were raised and the main issues, with which we are now

concerned, are Issues 1 and 2, and they are: (1) whether the adoption of Venkayya was true and

valid; and (2) whether Pitchayya and Chimpirayya were divided as alleged by the plaintiff. The

learned Subordinate Judge, after considering the entire oral and documentary evidence in the

case, came to the conclusion that the plaintiff had not established the factum of adoption of

Venkayya by her husband Pitchayya and that she also failed to prove that Chimpirayya and

Pitchayya were divided from each other; and in the result he dismissed the suit with costs.

4. On appeal, a Division Bench of the Andhra High Court reviewed the entire evidence over

again and affirmed the findings of the learned Subordinate Judge on both the issues. Before the

learned Judges another point was raised, namely, that the recitals in the will disclose a clear and

unambiguous declaration of the intention of Chimpirayya to divide, that the said declaration

constituted a severance in status enabling him to execute a will. The learned Judges rejected that

plea on two grounds, namely, (1) that the will did not contain any such declaration; and (2) that, if

it did, the plaintiff should have claimed a division of the entire family property, that is, not only

the property claimed by Chimpirayya but also the properly alleged to have been given to

Pitchayya and that the suit as framed would not be maintainable. In the result the appeal was

dismissed with costs. The present appeal has been preferred by the plaintiff by certificate against

the said judgment.

5. Learned Advocate-General of Andhra Pradesh, appearing for the appellant, raises before us

the following points: (1) The findings of the High Court on adoption as well as on partition were

vitiated by the High Court not drawing the relevant presumptions permissible in the case of old

transactions, not appreciating the great evidentiary value of public documents, ignoring or at any

rate not giving weight to admissions made by parties and witnesses and by adopting a mechanical

instead of an intellectual approach and perspective and above all ignoring the consistent conduct

of parties spread over a long period inevitably leading to the conclusion that the adoption and the

partition set up by the appellant were true. (2) On the assumption that there was no partition by

metes and bounds, the Court should have held on the basis of the entire evidence that there was a

division in status between Chimpirayya and Pitchayya, conferring on Chimpirayya the right to

bequeath his divided share of the family property. (3) The will itself contains recitals emphasizing

the fact that he had all through been a divided member of the family and that on the date of

execution of the will he continued to possess that character of a divided member so as to entitle

him to execute the will in respect of his share and, therefore, the recitals in the will themselves

constitute an unambiguous declaration of his intention to divide and the fact that the said

manifestation of intention was not communicated before his death to Subbarao or his guardian

Chenchamma could not affect his status as a divided member. And (4) Chenchamma, the

99

guardian of Subbarao, was present at the time of execution of the will and, therefore, even if

communication was necessary for bringing about a divided status, it was made in the present

case.

18. The next question is whether the concurrent finding of fact arrived at by the Courts below

on the question of partition calls for our interference. In the plaint neither the details of the

partition nor the date of partition are given. In the written-statement, the first respondent states

that Chimpirayya died undivided from his son Subbarao and so Subbarao got the entire property

by survivorship. The second issue framed was whether Chimpirayya and Pitchayya were divided

as alleged by the plaintiff. The partition is alleged to have taken place in or about the year 1895;

but no partition deed was executed to evidence the same. The burden is certainly on the appellant

who sets up partition to prove the said fact. PW 1, though she says that Veeranna was alive when

his sons effected the partition, admits that she was not present at the time of partition, but only

heard about it. PW 2, the appellant, deposes that her husband and his brothers effected partition

after she went to live with him; she adds that in that partition her father-in-law took about 4 acres

of land described as BangalaChenu subject to the condition that after his death it should be taken

by his four sons, that at the time of partition they drew up partition lists and recited that each

should enjoy what was allotted to him and that the lists were written by one

ManchellaNarasinhayya; she also admits that the lists are in existence, but she has not taken any

steps to have them produced in Court. She says that each of the brothers got pattas according to

the partition, and that the pattas got for Pitchayya’s share are in his house; yet she does not

produce them. She says that she paid kist for the lands allotted to Pitchayya’s share and obtained

receipts; but the receipts are not filed. She admits that she has the account books; but they have

not been filed in Court. On her own showing there is reliable evidence, such as accounts, Pattas,

receipts, partition lists and that they are available; but they are not placed before the Court. Her

interested evidence cannot obviously be acted upon when all the relevant evidence has been

suppressed.

22. Some argument is made on the question of burden of proof in the context of separation in

a family. The legal position is now very well settled. The Court in Bhagwati Prasad Shah v.

DulhinRameshwariJuer [(1951) SCR 603, 607], stated the law thus:

“The general principle undoubtedly is that a Hindu family is presumed to be joint

unless the contrary is proved, but where it is admitted that one of the coparceners did

separate himself from the other members of the joint family and had his share in the joint

property partitioned off for him, there is no presumption that the rest of the coparceneres

continued to be joint. There is no presumption on the other side too that because one

member of the family separated himself, there has been separation with regard to all. It

would be a question of fact to be determined in each case upon the evidence relating to

the intention of the parties whether there was a separation amongst the other coparceners

or that they remained united. The burden would undoubtedly lie on the party who asserts

the existence of a particular state of things on the basis of which he claims relief.”

100

Whether there is a partition in a Hindu joint family is, therefore, a question of fact;

notwithstanding the fact that one or more of the members of the joint family were separated from

the rest, the plaintiff who seeks to get a specified extent of land on the ground that it fell to the

share of the testator has to prove that the said extent of land fell to his share; but when evidence

has been adduced on both sides, the burden of proof ceases to have any practical importance. On

the evidence adduced in this case, both the Courts below found that there was no partition

between Chimpirayya and Pitchayya as alleged by the appellant. The finding is one of fact. We

have broadly considered the evidence only for the purpose of ascertaining whether the said

concurrent finding of fact is supported by evidence or whether it is in any way vitiated by errors

of law. We find that there is ample evidence for the finding and it is not vitiated by any error of

law.

23. Even so, learned Advocate-General contends that we should hold on the evidence that

there was a division in status between Chimpirayya and the other member of the joint Hindu

family i.e. Subbarao, before Chimpirayya executed the will, or at any rate on the date when he

executed it.

24. It is settled law that a member of a joint Hindu family can bring about his separation in

status by a definite and unequivocal declaration of his intention to separate himself from the

family and enjoy his share in severalty. Omitting the Will, the earlier documents filed in the case

do not disclose any such clear intention. We have already held that there was no partition between

Chimpirayya and Pitchayya. The register of changes on which reliance is placed does not indicate

any such intention. The statement of Chimpirayya that his younger brother’s son is a sharer in

some lands and, therefore, his name should be included in the register, does not ex facie or by

necessary implication indicate his unambiguous declaration to get divided in status from him. The

conflicting descriptions in various documents introduce ambiguity rather than clarity in the matter

of any such declaration of intention. Be it as it may, we cannot therefore hold that there is any

such clear and unambiguous declaration of intention made by Chimpirayya to divide himself

from Venkayya.

25. Now we shall proceed to deal with the will, Ex. A-2(a), on which strong reliance is placed

by the learned Advocate-General in support of his contention that on January 14, 1945, that is, the

date when the Will was executed, Chimpirayya must be deemed to have been divided in status

from his grandson Subbarao. A will speaks only from the date of death of the testator. A member

of an undivided coparcenary has the legal capacity to execute a will; but he cannot validly

bequeath his undivided interest in the joint family property. If he died as an undivided member of

the family, his interest survives to the other members of the family, and, therefore, the will cannot

operate on the interest of the joint family property. But if he was separated from the family before

his death, the bequest would take effect. So, the important question that arises is whether the

testator in the present case, became separated from the joint family before his death.

101

26. The learned Advocate-General raises before us the following contention in the alternative:

(1) Under the Hindu law a manifested fixed intention contradistinguished from an undeclared

intention unilaterally expressed by member to separate himself from the joint family is enough to

constitute a division in status and the publication of such a settled intention is only a proof

thereof. (2) Even if such an intention is to be manifested to the knowledge of the persons affected,

their knowledge dates back to the date of the declaration that is to say, the said member is deemed

to have been separated in status not on the date when the other members have knowledge of it but

from the date when he declared his intention. The learned Advocate-General, develops his

argument in the following steps: (1) The Will, Ex. A-2(a), contains as unambiguous intention on

the part of Chimpirayya to separate himself from Subbarao; (2) he manifested his declaration of

fixed intention to divide by executing the Will and that the Will itself was a proof of such an

intention; (3) when the Will was executed, the first respondent, the guardian of Subba Rao was

present and therefore, she must be deemed to have had knowledge of the said declaration; (4)

even if she had no such knowledge and even if she had knowledge of it after the death of

Chimpirayya, her knowledge dated back to the date when the Will was executed, and, therefore,

when Chimpirayya died he must be deemed to have died separated from the family with the result

that the Will would operate on his separate interest.

27. The main question of law that arises is whether a member of a joint Hindu family

becomes seperated from the other members of the family by mere declaration of his unequivocal

intention to divide from the family without bringing the same to the knowledge of the other

member of the family. In this context a reference to Hindu law texts would be appropriate, for

they are the sources from which Courts evolved the doctrine by a pragmatic approach to problems

that arose from time to time. The evolution of the doctrine can be studied in two parts, namely,

(1) the declaration of the intention, and (2) communication of it to others affected thereby.On the

first part the following texts would throw considerable light. They are collected and translated by

ViswanathaSastri, J., who has a deep and abiding knowledge of the sources of Hindu law in

AdiyalathKatheesumma v. AdiyalathBeechu[ILR 1930 Mad 502] and we accept his translations

as correct and indeed learned counsel on both sides proceeded on that basis. Yajnavalkya,

[Chapter II, Section 121]. “In land, corrody (annuity, etc.), or wealth received from the

grandfather, the ownership of the father and the son is only equal.” Vijnaneswara commenting on

the said sloka says:

“And thus though the mother is having menstrual courses (has not lost the capacity to

bear children) and the father has attachment and does not desire a partition, yet by the

will (or desire) of the son a partition of the grandfather’s wealth does take place.”

(Setlur’sMitakshara, [pp. 646-48].

SaraswatiVilase, placitum 28.

102

“From this it is known that without any speech (or explanation) even by means of a

determination (or resolution) only, partition is effected, just as an appointed daughter is

constituted by mere intention without speech.”

Viramitrodaya of Hitra Misra(Chapter II, Pl. 23).

“Here too there is no distinction between a partition during the lifetime of the father

or after his death and partition at the desire of the sons may take place or even by the

desire (or at the will of a single coparcener).

VyavaharaMayukha of Nilakantabhatta: (Chapter IV, Section iii-I).

“Even in the absence of any common (joint family) property, severance does indeed

result by the mere declaration “I am separate from thee” because severance is a particular

state (or condition) of the mind and the declaration is merely a manifestation of this

mental state (or condition).”

The Sanskrit expressions “sankalpa” (resolution) in Saraswati Vilas, “akechchaya” (will of single

coparcener) in Viramitrodaya “budhivisesha” (particular state or condition of the mind) in

VyavaharaMayukha, bring out the idea that the severance of joint status is a matter of individual

direction. The Hindu law texts, therefore, support the proposition that severance in status is

brought about by unilateral exercise of discretion.

28. Though in the beginning there appeared to be a conflict of views, the later decisions

correctly interpreted the Hindu law texts. This aspect has been considered and the law pertaining

thereto precisely laid down by the Privy Council in a series of decisions. In Syed Kasam v.

Jorawar Singh [(1922) ILR 50 Cal 84 (PC)], the Judicial Committee, after reviewing its earlier

decision laid the settled law on the subject thus:

“It is settled law that in the case of a joint Hindu family subject to the law of the

Mitakshara, a severance of estate is effected by an unequivocal declaration on the part of

one of the joint holders of his intention to hold his share separately, even though no

actual division takes place….”

So far, therefore, the law is well settled, namely, that a severance in estate is a matter of

individual discretion and that to bring about that state there should be an unambiguous declaration

to that effect are propositions laid down by the Hindu law texts and sanctioned by authoritative

decisions of Courts. But the difficult question is whether the knowledge of such a manifested

intention on the part of the other affected members of the family is a necessary condition for

constituting a division in status. Hindu law texts do not directly help us much in this regard,

except that the pregnant expressions used therein suggest a line of thought which was pursued by

Courts to evolve concepts to meet the requirements of a changing society. The following

statement in VyavaharaMayukha is helpful in this context:

103

“…severance does indeed result by the mere declaration” ‘I am separate from thee’

because severance is a particular state (or condition) of the mind and the declaration is

merely a manifestation of this mental state (or condition).”

One cannot declare or manifest his mental state in a vacuum. To declare is to make known, to

assert to others. “Others” must necessarily be those affected by the said declaration. Therefore a

member of a joint Hindu family seeking to separate himself from others will have to make known

his intention to the other members of the family from whom he seeks to separate. The process of

manifestation may vary with circumstances. This idea was expressed by learned Judges by

adopting different terminology, but they presumably found it as implicit in the concept of

declaration. SadasivaIyer,J., in Soun-dararaian v Arunachalam Chetty [(1915) ILR 39 Mad 159

(PC)] said that the expression “clearly expressed” used by the Privy Council in Suraj Narain v.

Iqbal Narain[(1912) ILR 35 All 80 (PC)] meant “clearly expressed to the definite knowledge of

the other coparceners”. In Girja Bai v. SadashiveDhundiraj [(1916) ILR 43 Cal 1031 (PC)], the

Judicial Committee observed that the manifested intention must be “clearly intimated” to the

other coparceners. Sir George Lownles in Bal Krishna v. Ram Ksishna [(1931) ILR 53 All 300

(PC)] took it as settled law that a separation may be effected by clear and unequivocal declaration

on the part of one member of a joint Hindu family to his coparceners of his desire to separate

himself from the joint family. Sir John Wallis in Babu Ramasray Prasad Choudhary v. Radhika

Devi [(1935) 43 LW 172 (PC)] again accepted as settled law the proposition that “a member of a

joint Hindu family may effect a separation in status by giving a clear and unmistakable intimation

by his acts or declaration of a fixed intention to become separate.…” Sir John Wallis, C.J., and

KumaraswamiSastri, J. in KamepalliAvilamma v. MannemVenkataswamy [(1913) 33 MLJ 746)]

were emphatic when they stated that if a coparcener did not communicate, during his life time, his

intention to become divided to the other coparceners, the mere declaration of his intention, though

expressed or manifested, did not effect a severance in status. These decisions authoritatively laid

down the proposition that the knowledge of the members of the family of the manifested intention

of one of them to separate from them is a necessary condition for bringing about that member’s

severance from the family. But it is said that two decisions of the Madras High Court registered a

departure from the said rule. The first of them is the decision of Madhavan Nair, J. in Rama

Ayyar v. Meenakshi Ammal [(1930) 33 LW 384]. There, the learned Judge held that severance of

status related back to the date when the communication was sent. The learned Judge deduced this

proposition from the accepted principle that the other coparceners had no choice or option in the

matter. But the important circumstance in that case was that the testator lived till after the date of

the service of the notice. If that was so, that decision on the facts was correct. We shall deal with

the doctrine of relating back at a later stage. The second decision is that of a Division Bench of

the Madras High Court, consisting of Varadachariar and King, JJ., in Narayana Rao v.

Purushotama Rao [ILR 1938 Mad 315, 318]. There, a testator executed a will disposing of his

share in the joint family property in favour of a stranger and died on August 5, 1926. The notice

sent by the testator to his son on August 3, 1926 was in fact received by the latter on August 9,

104

1926. It was contended that the division in status was effected only on August 9, 1926, when the

son received the notice and as the testator had died on August 5, 1926 and the estate had passed

by survivorship to the son on that date the receipt of the notice on August 9, 1926 could not divest

the son of the estate so vested in him and the will was, therefore, not valid. Varadachariar, J.,

delivering the judgment of the Bench observed thus:

“It is true that the authorities lay down generally that the communication of the

intention to become divided to other coparceners is necessary, but none of them lays

down that the severance in status does not take place till after such communication has

been received by the other coparceners.”

After pointing out the various anomalies that might arise in accepting the contention advanced

before them, the learned Judge proceeded to state:

“It may be that if the law is authoritatively settled, it is not open to us to refuse to

give effect to it merely on the ground that it may lead to anomalous consequences; but

when the law has not been so stated in any decision of authority and such a view is not

necessitated or justified by the reason of the rules, we see no reason to interpret the

reference to ‘communication’ in the various cases as implying that the severance does

not arise until notice has actually been received by the addressee or addressees.”

We regret our inability to accept this view. Firstly, because, as we have pointed out earlier, the

law has been well settled by the decisions of the Judicial Committee that the manifested intention

should be made known to the other members of the family affected thereby; secondly, because

there would be anomalies on the acceptation of either of the views. Thirdly, it is implicit in the

doctrine of declaration of an intention that it should be declared to somebody and who can that

somebody be except the one that is affected thereby.

31. We agree with the learned Judge insofar as he held that there should be an intimation,

indication or expression of the intention to become divided and that what form that manifestation

should take would depend upon the circumstances of each case. But if the learned Judge meant

that the said declaration without it being brought to the knowledge of the other members of the

family in one way or other constitutes a severance in status, we find it difficult to accept it. In our

view, it is implicit in the expression “declaration” that it should be to the knowledge of the person

affected thereby. An uncommunicated declaration is no better than a mere formation or

harbouring of an intention to separate. It becomes effective as a declaration only after its

communication to the person or persons who would be affected thereby.

32. It is, therefore, clear that Hindu law texts suggested and Courts evolved, by a process of

reasoning as well as by a pragmatic approach that, such a declaration to be effective should reach

the person or person affected by one process or other appropriate to a given situation.

33. This view does not finally solve the problem. There is yet another difficulty. Granting that

a declaration will be effective only when it is brought to the knowledge of the other members

affected, three question arise namely, (i) how should the intention be conveyed to the other

105

member or members; (ii) when it should be deemed to have been brought to the notice of the

other member or members; and (iii) when it was brought to their notice, would it be the date of

the expression of the intention or that of knowledge that would be crucial to fix the date of

severance. The questions posed raise difficult problems in a fast changing society. What was

adequate in a village polity when the doctrine was conceived and evolved can no longer meet the

demands of a modern society. Difficult questions, such as the mode of service and its sufficiency,

whether a service on a manager would be enough, whether service on the major members or a

substantial body of them would suffice, whether notice should go to each one of them, how to

give notice to minor members of the family, may arise for consideration. But, we need not

express our opinion on that said questions, as nothing turns upon them, for in this appeal there are

only two members in the joint family and it is not suggested that Subba Rao did not have the

knowledge of the terms of the will after the death of Chimpirayya.

34. The third question to be decided in this appeal is this: what is the date from which

severance in status is deemed to have taken place? Is it the date of expression of intention or the

date when it is brought to the knowledge of the other members? If it is the latter date, is it the date

when one of the members first acquired knowledge or the date when the last of them acquired the

said knowledge or the different dates on which each of the members of the family got knowledge

of the intention so far as he is concerned? If the last alternative be accepted, the dividing member

will be deemed to have been separated from each of the members on different dates. The

acceptance of the said principle would inevitably lead to confusion. If the first alternative be

accepted, it would be doing lip service to the doctrine of knowledge, for the member who gets

knowledge of the intention first may in no sense of the term be a representative of the family. The

second alternative may put off indefinitely the date of severance, as the whereabouts of one of the

members may not be known at all or may be known after many years. The Hindu law texts do not

provide any solution to meet these contingencies. The decided cases also do not suggest a way

out. It is, therefore, open to this Court to evolve a reasonable and equitable solution without doing

violence to the principles of Hindu law. The doctrine of relation back has already been recognized

by Hindu law developed by courts and applied in that branch of the law pertaining to adoption.

There are two ingredients of a declaration of a member’s intention to separate. One is the

expression of the intention and the other is bringing the expression to the knowledge of the person

or persons affected. When once the knowledge is brought home – that depends upon the facts of

each case – it relates back to the date when the intention is formed and expressed. But between the

two dates, the person expressing the intention may lose his interest in the family property; he may

withdraw his intention to divide; he may die before his intention to divide is conveyed to the

other members of the family: with the result his interest survives to the other members. A

manager of a joint Hindu family may sell away the entire family property for debts binding on the

family. There may be similar other instances. If the doctrine of relation back is invoked without

any limitation thereon, vested rights so created will be affected and settled titles may be

disturbed. Principles of equity require and common sense demands that a limitation which avoids

106

the confusion of titles must be placed on it. What would be more equitable and reasonable than to

suggest that the doctrine should not affect vested rights? By imposing such a limitation we are not

curtailing the scope of any well established Hindu law doctrine, but we are invoking only a

principle by analogy subject to a limitation to meet a contingency. Further, the principle of

retroactivity, unless a legislative intention is clearly to the contrary, saves vested rights. As the

doctrine of relation back involves retroactivity by parity of reasoning, it cannot affect vested

rights. It would follow that, though the date of severance is that of manifestation of the intention

to separate the right accrued to others in the joint family property between the said manifestation

and the knowledge of it by the other members would be saved.

35. Applying the said principles to the present case, it will have to be held that on the death of

Chimpirayya his interest devolved on Subbarao and, therefore, his will, even if it could be relied

upon for ascertaining his intention to separate from the family, could not convey his interest in

the family property, as it has not been established that Subbarao or his guardian had knowledge of

the contents of the said will before Chimpirayya died.

36. It is contended that the first respondent, as the guardian of Subbarao, had knowledge of

the contents of the Will and, therefore, the Will operates on the interest of Chimpirayya. Reliance

is placed upon the evidence of PW 11, one KomanduriSingaracharyulu. He deposed that he was

present at the time the Will was executed by Chimpirayya and that he signed it as an identifying

witness. In the cross-examination he said that at the time of the execution of the Will the first

defendant-respondent was inside the house. This evidence is worthless. The fact that she was

inside the house cannot in itself impute to her the knowledge of the contents of the Will or even

the fact that the Will was registered that day. DW 4 is the first respondent herself. She says in her

evidence that she did not know whether the Sub-Registrar came to register the Will of

Chimpirayya, and that she came to know of the Will only after the suit was filed. In that state of

evidence it is not possible to hold that the first respondent, as guardian of Suobarao, had

knowledge of the contents, of the Will. In the result, the appeal fails and is dismissed.