Case Summary

| Citation | Jumma Masjid, Mercara v. Kodimaniandra DeviahAIR 1962 SC 847 : 1962 Supp (1) SCR 554 |

| Keywords | Sec 6(a), 43 TPA. Feeding the grant by estoppel |

| Facts | A Hindu joint family consisted of three brothers Br 1, Br 2, Br 3 and one sister Si. Brothers one died unmarried, and the other two died one after another, leaving behind their widows W 2 and W 3, but no children. Sister, who had three grandsons A, B and C, who were the reversioners to their property, they would get the property but on the death of the two widows. Till the death of the widows, the interest that they had in the property was a mere spes successionis, that according to s. 6(a) is untransferable. However, they represented to the transferee that this property belonged to the joint family and after the death of W 2, it devolved on them as reversioners, and hence they were competent to transfer the same. They did not disclose the fact that W 3 was still alive. W 3 resisted the suit of transferee for possession of property on the ground that till she was alive, and no one else has a right to possess the property. W 3 died later, and the transferee applied before the revenue authorities for transferring the patta for the property standing in the name of W 3 to his name on the strength of the sale deed executed by the reversioners. At this time, Jumma Masjid intervened and contended that first, the whole of the properties vested in them on the strength of a gift deed executed by W 3 in their favour, and secondly, they alleged that one of the reversioners, A, had relinquished his share in the property in their favour for a consideration of R s. 300. The contention of Jumma Masjid was that s. 43 must be read as subject to the provisions of s. 6(a), that specifically prohibits the transfer of spes successions and therefore s. 43 should apply only in cases other than those covered under s. 6(a). |

| Issues | Whether a transfer of property, in return for some consideration made by a person who represents that he has a present and transferable interest in that property, while in reality he possess only a spec succession, is within the protection of sec 43 tpa? |

| Contentions | |

| Law Points | Ganpathi (transferee) contended that he had no knowledge about the seller’s ownership title over the property as they misled him by claiming to be the actual owner. However, after the death of W3, they gained actual possession of it, and now the rule of estoppel applies, entitling him to get the title of the property. The Apex Court observed that Sections 6(a) and 43 are two different subjects: Section 6(a) deals with certain interests in property and prohibits the interest, but Section 43 deals with representations as to title made by a transferor who had no title at the time of transfer. Section 6(a) enacts a rule of substantive law, whereas Section 43 enacts a rule of estoppel, which is one of evidence. The court observed that the claim of Ganpathi is valid. |

| Judgement | Court held that when a person transfers property representing himself of having present interest in that property, whereas he has only spes successionis, then transferee will get benefit of sec 43, if he has represent himself and transfer for consideration. |

| Ratio Decidendi & Case Authority |

Full Case Details

VENKATARAMA AIYAR, J. – This is an appeal against the Judgment of the High Court of

Madras, dismissing the suit filed by the appellant, as Muthavalli of the Jumma Masjid, Mercara, for

possession of a half-share in the properties specified in the plaint. The facts are not in dispute. There

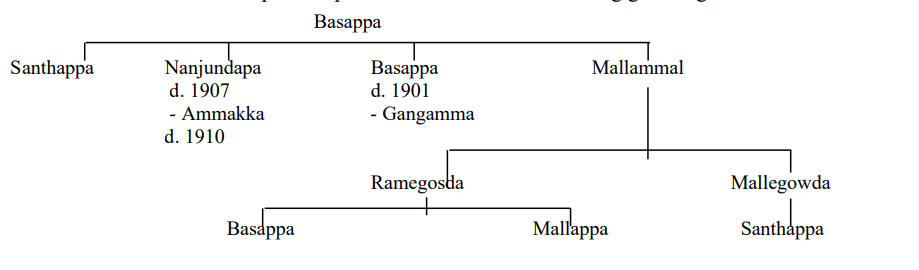

was a joint family consisting of three brothers, Santhappa, Nanjundappa and Basappa. Of these,

Santhappa died unmarried, Basappa died in 1901, leaving behind a widow Gangamma, and

Nanjundappa died in 1907 leaving him surviving his widow Ammakka, who succeeded to all the

family properties as his heir. On the death of Ammakka, which took place in 1910, the estate

devolved on Basappa, Mallappa and Santhappa, the sister’s grandsons of Nanjundappa as his next

reversioners. The relationship of the parties is shown in the following genealogical table.

2. On August 5, 1900, Nanjundappa and Basappa executed a usufructuary mortgage over the

properties which form the subject-matter of this litigation, and one Appanna Shetty, having obtained

an assignment thereof, filed a suit to enforce it, OS 9 of 1903, in the court of the Subordinate Judge,

Coorg. That ended in a compromise decree, which provided that Appanna Shetty was to enjoy the

usufruct from the hypotheca till August 1920, in full satisfaction of all his claims under the mortgage,

and that the properties were thereafter to revert to the family of the mortgagors. By a sale deed dated

November 18, 1920, Ex. III, the three reversioners, Basappa, Mallappa and Santhappa, sold the suit

properties to one Ganapathi, under whom the respondents claim, for a consideration of Rs 2000.

Therein the vendors recite that the properties in question belonged to the joint family of Nanjundappa

and his brother Basappa, that on the death of Nanjundappa, Ammaka inherited them as his widow,

and on her death, they had devolved on themselves the next reversioners of the last male owner. On

March 12, 1921, the vendor executed another deed, Ex. IV, by which Ex. III was rectified by

inclusion of certain items of properties, which were stated to have been left out by oversight. It is on

these documents that the title of the respondents rests.

3. On the strength of these two deeds, Ganapathi sued to recover possession of the properties

comprised therein. The suit was contested by Gangamma, who claimed that the properties in question

were the self-acquisitions of her husband Basappa, and that she, as his heir, was entitled to them. The

Subordinate Judge of Coorg who tried the suit accepted this contention, and his finding was affirmed

by the District Judge on appeal, and by the Judicial Commissioner in second appeal. But before the

second appeal was finally disposed of, Gangamma died on February 17, 1933. Thereupon Ganapathi

applied to the Revenue Authorities to transfer the patta for the lands standing in the name of

Gangamma to his own name, in accordance with the sale deed Ex. III. The appellant intervened in

77

these proceedings and claimed that the Jumma Masjid, Mercara, had become entitled to the

properties held by Gangamma, firstly, under a Sadakah or gift alleged to have been made by her on

September 5, 1932, and, secondly, under a deed of release executed on March 3, 1933, by Santhappa,

one of the reversioners, relinquishing his half-share in the properties to the mosque for a consideration

of Rs 300. By an order dated September 9, 1933, Ex. II, the Revenue Authorities declined to accept

the title of the appellant and directed that the name of Ganapathi should be entered as the owner of the

properties. Pursuant to this order, Ganapathi got into possession of the properties.

4. The suit out of which the present appeal arises was instituted by the appellant on January 2,

1945, for recovery of a half-share in the properties that had been held by Gangamma and for mesne

profits. In the plaint, the title of the appellant to the properties is based both on the gift which

Gangamma is alleged to have made on September 5, 1932, and on the release deed executed by

Santhappa, the reversioner, on March 3, 1933. With reference to the title put forward by the

respondents on the basis of Ex. III and Ex. IV, the claim made in the plaint is that as the vendors had

only a spes successionis in the properties during the lifetime of Gangamma. the transfer was void and

conferred no title. The defence of the respondents to the suit was that as Santhappa had sold the

properties to Ganapathi on a representation that he had become entitled to them as reversioner of

Nanjundappa, on the death of Ammakka in 1910, he was estopped from asserting that they were in

fact the self-acquisitions of Basappa, and that he had, in consequence, no title at the dates of Ex. III

and Ex. IV. The appellant, it was contended, could, therefore, get no title as against them under the

release deed, Ex. A, dated March 3, 1933.

5. The District Judge of Coorg who heard the action held that the alleged gift by Gangamma on

September 5, 1932, had not been established, and as this ground of title was abandoned by the

appellant in the High Court, no further notice will be taken of it. Dealing next with the title claimed by

the appellant under the release deed, Ex. A, executed by Santhappa, the District Judge held that as

Ganapathi had purchased the properties under Ex. III on the faith of the representation contained

therein that the vendors had become entitled to them on the death of Ammakka in 1910, he acquired a

good title under Section 43 of the Transfer of Property Act, and that Ex. A could not prevail as against

it. He accordingly dismissed the suit. The plaintiff took the matter in appeal to the High Court,

Madras, and in view of the conflict of authorities on the question in that Court, the case was referred

for the decision of a Full Bench. The learned Judges who heard the reference agreed with the court

below that the purchaser under Ex. III had, in taking the sale, acted on the representation as to title

contained therein, and held that as the sale by the vendors was of properties in which they claimed a

present interest and not of a mere right to succeed in future, Section 43 of the Transfer of Property Act

applied, and the sale became operative when the vendors acquired title to the properties on the death

of Gangamma on February 17, 1933. In the result, the appeal was dismissed. The appellant then

applied for leave to appeal to this Court under Article 133(l)(c), and the same was granted by the High

Court of Mysore to which the matter had become transferred under Section 4 of Act 72 of 1952.

6. The sole point for determination in this appeal is, whether a transfer of property for

consideration made by a person who represents that he has a present and transferable interest therein,

while he possesses, in fact, only a spes successionis, is within the protection of Section 43 of the

Transfer of Properly Act. If it is, then on the facts found by the courts below, the title of the

respondents under Ex. III and Ex. IV must prevail over that of the appellant under Ex. A. If it is not,

then the appellant succeeds on the basis of Ex. A. Considering the scope of the section on its terms, it

clearly applies whenever a person transfers property to which he has no title on a representation that

78

he has a present and transferable interest therein, and acting on that representation, the transfree

takes a transfer for consideration. When these conditions are satisfied, the section enacts that if the

transferor subsequently acquires the property, the transferee becomes entitled to it, if the transfer has

not in the meantime been thrown up or cancelled and is subsisting. There is an exception in favour of

transferees for consideration in good faith and without notice of the rights under the prior transfer. But

apart from that, the section is absolute and unqualified in its operation. It applies to all transfers which

fulfil the conditions prescribed therein, and it makes no difference in its application, whether the

defect of title in the transferor arises by reason of his having no interest whatsoever in the property, or

of his interest therein being that of an expectant heir.

8. The contention on behalf of the appellant is that Section 43 must be read subject to Section 6(a)

of the Transfer of Property Act which enacts that: “The chance of an heir apparent succeeding to an

estate, the chance of a relation obtaining a legacy on the death of a kinsman or any other mere

possibility of a like nature, cannot be transferred”. The argument is that if Section 43 is to be

interpreted as having application to cases of what are in fact transfers of spes successionis, that will

have the effect of nullifying Section 6 (a), and that therefore it would be proper to construe Section 43

as limited to cases of transfers other then those falling within Section 6(a). In effect, this argument

involves importing into the section a new exception to the following effect: “Nothing in this section

shall operate to confer on the transferee any title, if the transferor had at the date of the transfer an

interest of the kind mentioned in Section 6(a)”. If we accede to this contention, we will not be

construing Section 43, but rewriting it. “We are not entitled”, observed Lord Loreburn L.C., in

Vickers v. Evans [(1910) 79 LJ KB 954] “to read words into an Act of Parliament unless clear reason

for it is to be found within the four corners of the Act itself”.

9. Now the compelling reason urged by the appellant for reading a further exception in Section 43

is that if it is construed as applicable to transfers by persons who have only spes successionis at the

date of transfer, it would have the effect of nullifying Section 6(a). But Section 6(a) and Section 43

relate to two different subjects, and there is no necessary conflict between them. Section 6(a) deals

with certain kinds of interests in property mentioned therein, and prohibits a transfer simpliciter of

those interests. Section 43 deals with representations as to title made by a transferor who had no title

at the time of transfer, and provides that the transfer shall fasten itself on the title which the transferor

subsequently acquires. Section 6(a) enacts a rule of substantive law, while Section 43 enacts a rule of

estoppel which is one of evidence. The two provisions operate on different fields, and under different

conditions, and we see no ground for reading a conflict between them or for cutting down the ambit of

the one by reference to the other. In our opinion, both of them can be given full effect on their own

terms, in their respective spheres. To hold that transfers by persons who have only a spes successionis

at the date of transfer are not within the protection afforded by Section 43 would destroy its utility to a

large extent.

10. It is also contended that as under the law there can be no estoppel against a statute, transfers

which are prohibited by Section 6(a) could not be held to be protected by Section 43. There would

have been considerable force in this argument if the question fell to be decided solely on the terms of

Section 6(a). Rules of estoppel are not to be resorted to for defeating or circumventing prohibitions

enacted by statutes on grounds of public policy. But here the matter does not rest only on Section

6(a). We have, in addition, Section 43, which enacts a special provision for the protection of

transferees for consideration from persons who represent that they have a present title, which, in fact,

they have not. And the point for decision is simply whether on the facts the respondents are entitled to

79

the benefit of this section. If they are, as found by the court below, then the plea of estoppel raised

by them on the terms of the section is one pleaded under, and not against the statute.

12. So far we have discussed the question on the language of the section and on the principles

applicable thereto. There is an illustration appended to Section 43, and we have deferred consideration

thereof to the last as there has been a controversy as to how far it is admissible in construing the

section. It is as follows:

“A, a Hindu, who has separated from his father B, sells to C three fields, X, Y and Z,

representing that A is authorized to transfer the same. Of these fields Z does not belong to A,

it having been retained by B on the partition; but on B dying, A as heir obtains Z. C, not

having rescinded the contract of sale, may require A to deliver Z to him”.

In this illustration, when A sold the field Z to C, he had only a spes successionis. But he having

subsequently inherited it, C became entitled to it. This would appear to conclude the question against

the appellant. But it is argued that the illustration is repugnant to the section and must be rejected. If

the language of the section clearly excluded from its purview transfers in which the transferor had

only such interest as is specified in Section 6(a), then it would undoubtedly not be legitimate to use

the illustration to enlarge it. But far from being restricted in its scope as contended for by the

appellant, the section is, in our view, general in its terms and of sufficient amplitude to take in the

class of transfers now in question. It is not to be readily assumed that an illustration to a section is

repugnant to it and rejected. Reference may, in this connection, be made to the following observations

of the Judicial Committee in Mahomed Syedol Ariffin v. Yeoh Ooi Gark [AIR 1916 PC 242] as to the

value to be given to illustrations appended to a section, in ascertaining its true scope:

“It is the duty of a court of law to accept, if that can be done, the illustrations given as

being both of relevance and value in the construction of the text. The illustrations should in no

case be rejected because they do not square with ideas possibly derived from another system

of jurisprudence as to the law with which they or the sections deal. And it would require a

very special case to warrant their rejection on the ground of their assumed repugnancy to the

sections themselves. It would be the very last resort of construction to make any such

assumption. The great usefulness of the illustrations, which have, although not part of the

sections, been expressly furnished by the legislature as helpful in the working and application

of the statute, should not be thus impaired”.

13. We shall now proceed to consider the more important cases wherein the present question has

been considered. One of the earliest of them is the decision of the Madras High Court in Alamanaya

Kunigari Nabi Sab v. Murukuti Papiah [AIR 1915 Mad 972]. That arose out of a suit to enforce a

mortgage executed by the son over properties belonging to the father, while he was alive. The father

died pending the suit, and the properties devolved on the son as his heir. The point for decision was

whether the mortgagee could claim the protection of Section 43 of the Transfer of Property Act. The

argument against it was that “Section 43 should not be so construed as to nullify Section 6(a) of the

Transfer of Property Act, by validating a transfer initially void under Section 6(a)”. In rejecting this

contention, the court observed:

“This argument, however, neglects the distinction between purporting to transfer ‘the

chance of an heir-apparent’, and ‘erroneously representing that he (the transferor) is

authorised to transfer certain immovable property’. It is the latter course that was followed in

80

the present case. It was represented to the transferee that the transferor was in praesenti entitled

to and thus authorise to transfer the property”. (p.736)

On this reasoning, if a transfer is statedly of an interest of the character mentioned in Section 6(a),

it would be void, whereas, if it purports to be of an interest in praesenti, it is within the protection

afforded by Section 43.

14. Then we come to the decision in The Official Assignee, Madras v. Sampath Naidu [AIR

1933 Mad 795], where a different view was taken. The facts were that one V. Chetti had executed two

mortgages over properties in respect of which he had only spes successionis. Then he succeeded to

those properties as heir and then sold them to one Ananda Mohan. A mortgagee claiming under

Ananda Mohan filed a suit for a declaration that the two mortgages created by Chetty before he had

become entitled to them as heir, were void as offending Section 6(a) of the Transfer of Property Act.

The mortgagee contended that in the events that had happened the mortgages had become enforceable

under Section 43 of the Act. The court negatived this contention and held that as the mortgages, when

executed, contravened Section 6(a), they could not become valid under Section 43. Referring to the

decision in Alamanaya Kunigari Ndbi Sab v. Murukuti Papiah, the court observed that no

distinction could be drawn between a transfer of what is on the face of it spes successionis, and what

purports to be an interest in praesenti. “If such a distinction were allowed”, observed Bardswell, J.,

delivering the Judgment of the court. “the effect would be that by a clever description of the property

dealt with in a deed of transfer one would be allowed to conceal the real nature of the transaction and

evade a clear statutory prohibition”.

15. This reasoning is open to the criticism that it ignores the principle underlying Section 43. That

section embodies, as already stated, a rule of estoppel and enacts that a person who makes a

representation shall not be heard to allege the contrary as against a person who acts on that

representation. It is immaterial whether the transferor acts bona fide or fraudulently in making the

representation. It is only material to find out whether in fact the transferee has been misled. It is to be

noted that when the decision under consideration was given, the relevant words of Section 43 were,

“where a person erroneously represents”, and now, as amended by Act 20 of 1929, they are “where a

person fraudulently or erroneously represents”, and that emphasises that for the purpose of the section

it matters not whether the transferor acted fraudulently or innocently in making the representation, and

that what is material is that he did make a representation and the transferee has acted on it. Where the

transferee knew as a fact that the transferor did not possess the title which he represents he has, then

be cannot be said to have acted on it when taking a transfer. Section 43 would then have no

application, and the transfer will fail under Section 6(a). But where the transferee does act on the

representation, there is no reason why he should not have the benefit of the equitable doctrine

embodied in Section 43, however fraudulent the act of the transferor might have been.

16. The learned Judges were further of the opinion that in view of the decision of the Privy

Council in Ananda Mohan Roy v. Gour Mohan Mullick [AIR 1923 PC 189] and the decision in Sri

Jagannada Raju v. Sri Rajah Prasada Rao [AIR 1916 Mad 579] which was approved therein, the

illustration to Section 43 must be rejected as repugnant to it. In Sri Jagannada Raju case, the

question was whether a contract entered into by certain presumptive reversioners to sell the estate

which was then held by a widow as heir could be specifically enforced, after the succession had

opened. It was held that as Section 6(a) forbade transfers of spes successionis, contracts to make such

transfers would be void under Section 23 of the Contract Act, and could not be enforced. This

decision was approved by the Privy Council in Ananda Mohan Roy v. Gour Mohan Mullick where

81

also the question was whether a contract by the nearest reversioner to sell property which was in the

possession of a widow as heir was valid and enforceable, and it was held that the prohibition under

Section 6(a) would become futile, if agreements to transfer could be enforced. These decisions have

no bearing on the question now under consideration, as to the right of a person who for consideration

takes a transfer of what is represented to be an interest in praesenti. The decision in Official Assignee,

Madras v. Sampath Naidu is, in our view, erroneous, and was rightly overruled in the decision now

under appeal.

17. Proceeding on to the decisions of the other High Courts, the point under discussion arose

directly for decision in Shyam Narain v. Mangal Prasad [(1935) ILR 57 All 474]. The facts were

similar to those in Official Assignee, Madras v. Sampath Naidu. One Ram Narayan, who was the

daughter’s son of the last male owner, sold the properties in 1910 to the respondents, while they were

vested in the daughter’ Akashi. On her death in 1926, he succeeded to the properties as heir and sold

them in 1927 to the appellants. The appellants claimed the estate on the ground that the sale in 1910

conferred no title on the respondents as Ram Narayan had then only a spes successionis. The

respondents contended that they become entitled to the properties when Ram Narayan acquired them

as heir in 1926. The learned Judges, Sir S.M. Sulaiman, C.J., and Rachhpal Singh, J., held, agreeing

with the decision in Alamanaya Kunigari Nabi Sab v. Murukuti Papiah, and differing from The

Official Assignee, Madras v. Sampath Naidu and Bindeshwari Singh v. Har Narain Singh [AIR

1929 Oudh 185] that Section 43 applied and that the respondents had acquired a good title. In coming

to this conclusion, they relied on the illustration to Section 43 as indicating its true scope, and

observed:

“Section 6(a) would, therefore, apply to cases where professedly there is a transfer of a

mere spes successionis, the parties knowing that the transferor has no more right than that of a

mere expectant heir. The result, of course, would be the same where the parties knowing the

full facts fraudulently clothe the transaction in the garb of an out and out sale of the property,

and there is no erroneous representation made by the transferor to the transferee as to his

ownership.

But where an erroneous representation is made by the transferor to the transferee that he is

the full owner of the property transferred and is authorized to transfer it and the property

transferred is not a mere chance of succession but immovable property itself, and the

transferee acts upon such erroneous representation, then if the transferor happens later, before

the contract of transfer comes to an end, to acquire an interest in that property, no matter

whether by private purchase, gift, legacy or by inheritance or otherwise, the previous transfer

can at the option of the transferee operate on the interest which has been subsequently

acquired, although it did not exist at the time of the transfer”.

18. The preponderance of judicial opinion is in favour of the view taken by the Madras High

Court in Alamanaya Kunigari Nabi Sab v. Murukuti Papiah, and approved by the Full Bench in the

decision now under appeal. In our judgment, the interpretation placed on Section 43 in those decisions

is correct, and the contrary opinion is erroneous. We accordingly hold that when a person transfers

property representing that he has a present interest therein, whereas he has, in fact, only a spes

successionis, the transferee is entitled to the benefit of Section 43, if he has taken the transfer on the

faith of that representation and for consideration. In the present case, Santhappa, the vendor in Ex. III,

represented that he was entitled to the property in praesenti, and it has been found that the purchaser

entered into the transaction acting on that representation. He therefore acquired title to the properties

82

under Section 43 of the Transfer of Property Act, when Santhappa became in titulo on the death of

Gangamma on February 17, 1933, and the subsequent dealing with them by Santhappa by way of

release under Ex. A did not operate to vest any title in the appellant.

19. The Courts below were right in upholding the title of the respondents, and this appeal must be

dismissed with costs of the third respondent, who alone appears.