Case Summary

| Citation | Puttrangamma v. M.S. Ranganna(1968) 3 SCR 119, AIR 1968 SC 1018 |

| Keywords | Partition |

| Facts | Karta (Ranganna) of The family running family business and admitted to hospital he has 4 daughters. He issued a notification through post office for partition. Plaintiff told the post office to withdraw the notification and don’t want to get partition. Then plaintiff filed the complaint in Jan 1951, seeking division of his portion. Plaintiff instituted a suit(plaint) for partition of the property. Trial Court said Thumb impression was affixed when Karta was conscious and sound mind and hence the plaint was valid. High Court reversed the order and said there was evidence showing that communication made to defendant. |

| Issues | Whether the Ranganna died as separate member of joint family? Whether the plaint was valid? |

| Contentions | |

| Law Points | Joint property can be separate when it was communicate to other family members. There should be clear and unambiguous intention for partition, once the communication is done, then property or family will get separated. There was sufficient evidence to prove that the Karta wanting separation was conscious and not under pressure or any unsoundness of mind. Communication was done and property is separated. |

| Judgement | Court upheld the Trial court’s findings and held that plaint was valid. Plaint was submitted when plaintiff was in a sound mind and could grasp the contents of the plaint. Hence, property is separated now. |

| Ratio Decidendi & Case Authority |

Full Case Details

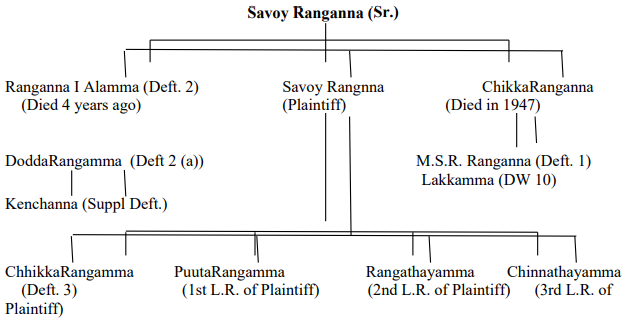

V. RAMASWAMI, J. – 2. The appellants and Respondent 4 are the daughters and legal

representatives of Savoy Ranganna who was the plaintiff in OS 34 of 1950-51 instituted in the

Court of the District Judge, Mysore. The suit was filed by the deceased plaintiff for partition of

his share in the properties mentioned in the schedule to the plaint and for granting him separate

possession of the same. Respondent 1 is the brother’s son of the Plaintiff. The relationship of the

parties would appear from the following pedigree:

3. The case of the plaintiff was that he and the defendants lived together as members of a

joint Hindu family till January 7, 1951, plaintiff being the karta. The plaintiff had no male issue

but had only four daughters, ChikkaRangamma, PuttaRangamma, Rangathayamma and

Chinnathayamma. The first 2 daughters were widows. The fourth daughter Chinnathayamma was

living with her husband. Except Chinnathayamma, the other daughters with their families had

been living with the joint family. The plaintiff became ill and entered Sharda Nursing Home for

treatment as an in-patient on January 4, 1951. In order to safeguard the interests of his daughters

the plaintiff, Savoy Ranganna issued a notice on January 8, 1951 to the defendants declaring his

unequivocal intention to separate from them. After the notices were registered at the post office

certain well-wishers of the family intervened and wanted to bring about a settlement. On their

advice and request the plaintiff notified to the post office that he intended to withdraw the

registered notices. But as no agreement could be subsequently reached between the parties the

plaintiff instituted the present suit on January 13, 1951 for partition of his share of the joint family

108

properties. The suit was contested mainly by Respondent 1 who alleged that there was no

separation of status either because of the notice of January 8, 1951 or because of the institution of

the suit on January 13, 1951. The case of Respondent 1 was that Savoy Ranganna was 85 years of

age and in a weak state of health and was not in a position to understand the contents of the plaint

or to affix his signature or thumb impression thereon as well as on the vakalatnama. As regards

the notice of January 8, 1951, Respondent 1 asserted that there was no communication of any

such notice to him and, in any case, the notices were withdrawn by Savoy Ranganna

unconditionally from the post office. It was therefore contended that there was no disruption of

the joint family at the time of the death of Savoy Ranganna and the appellants were not entitled to

a decree for partition as legal representatives of Savoy Ranganna. Upon the examination of the

evidence adduced in the case the trial court held that Savoy Ranganna had properly affixed his

thumb impression on the plaint and the Vakalatnama and the presentation of the plaint was valid.

The trial court found that Savoy Ranganna was not dead by the time the plaint was presented. On

the question whether Savoy Ranganna was separate in status the trial court held that the notices

dated January 8, 1951 were a clear and unequivocal declaration of the intention of Savoy

Ranganna to become divided in status and there was sufficient communication of that intention to

Respondent 1 and other members of the family. The trial court was also of the opinion that at the

time of the issue of the notices dated January 8, 1951 and at the time of execution of the plaint

and the Vakalatnama dated January 13, 1951 Savoy Ranganna was in a sound state of mind and

conscious of the consequences of the action he was taking. The trial court accordingly granted a

decree in favour of the appellants. Respondent 1 took the matter in appeal to the Mysore High

Court which by its judgment dated December 5, 1960 reversed the decree of the trial court and

allowed the appeal. Hegde, J. one of the members of the Bench held that the suit could not be said

to have been instituted by Savoy Ranganna as it was not proved that Savoy Ranganna executed

the plaint. As regards the validity of the notice Ex. A, and as to whether it caused any disruption

in the joint family status, Hegde, J. did not think it necessary to express any opinion. The other

member of the Bench, Mir Iqbal Husain, J., held that the joint family of which the deceased

Savoy Ranganna was a member had not been disrupted by the issue of the notice dated January 8,

1951. The view taken by Mir Iqbal Husain, J. was that there was no proof that the notice was

communicated either to Respondent 1 or to other members of the family and, in any event, the

notice had been withdrawn by Savoy Ranganna and so there was no severance of joint status from

the date of the notice.

4. The first question to be considered in this appeal is whether Savoy Ranganna died as a

divided member of the joint family as alleged in the plaint. It is admitted that Savoy Ranganna

was very old, about 85 years of age and was ailing of chronic diarrhoea. He was living in the

family house till January 4, 1951 when he was removed to the Sharda Nursing Home where he

died on January 13, 1951 at 3 p.m. According to the case of Respondent 1 Savoy Ranganna had a

paralytic stroke in 1950 and was completely bed-ridden thereafter and his eyesight was bad for 5

to 6 years prior to his death. It was alleged in the written statement that Savoy Ranganna was

109

unconscious for some days prior to his death. The case of Respondent 1 on this point is disproved

by the evidence of DW 6, Dr Venkata Rao who was in charge of the Sharda Nursing Home on the

material dates. This witness admitted that the complaint of Savoy Ranganna was that he was

suffering from chronic diarrhoea for over five months. He was anaemic but he was not suffering

from any attack of paralysis. As regards the condition of Savoy Ranganna on January 8, 1951, the

evidence of PW 1, Dr Subbaramiah is important. This witness is the owner of the Sharda Nursing

Home and he has testified that the notice Ex. A was read over to Savoy Ranganna and after

getting it read the latter affixed his thumb mark thereon. The witness asked Savoy Ranganna

whether he was able to understand the contents of the notice and the latter replied in the

affirmative. The witness has certified on the notice, Ex. A-1 that Savoy Ranganna was conscious

when he affixed his left thumb mark, to the notice in his presence. No reason was suggested on

behalf of the respondents why the evidence of this witness should be disbelieved. The trial court

was highly impressed by the evidence of this witness and we see no reason for taking a different

view. The case of the appellants is that Respondent 1 had knowledge of the notice, Ex. A because

he was present in the Nursing Home on January 8, 1951 and he tried to snatch away the notice

from the hands of PW 1 but he was prevented from so doing. PW 5, Chinnanna stated in the

course of the evidence that after PW 1 had signed the certificate in all the three copies,

Respondent 1 and one Halappa came to the ward and tried to snatch away the notices. The first

respondent tried to snatch away the copy Ex. A-1 that was in the hands of Dr Subbaramiah and

attempted to tear it. Dr Subbaramiah somehow prevented Respondent 1 from taking away Ex. A

and handed it over to PW 5. The evidence of PW 5 with regard to the “snatching incident” is

corroborated by Dr Subbaramiah who stated that after Savoy Ranganna had executed the notices

and he had signed the certificates, one or two persons came and tried to snatch the document. PW

1 is unable to identify the first respondent as one of the persons who had taken part in the

“snatching incident”. The circumstance that PW 1 was unable to identify Respondent 1 is not

very material, because the incident took place about three years before he gave evidence in the

court, but his evidence with regard to the “snatching incident” strongly corroborates the allegation

of PW 5 that it was Respondent 1 who had come into the Nursing Home and attempted to snatch

the notice. There is also another circumstance which supports the case of the appellants that

Respondent 1 had knowledge of the contents of Ex. A and of the unequivocal intention of Savoy

Ranganna to become divided in status from the joint family.

According to PW 5 Respondent 1 and his wife and mother visited SavoyRanganna in the

Nursing Home later on and pressed him to withdraw the notices promising that the matter will be

amicably settled. Sowcar T. Thammanna also intervened on their behalf. Thereafter the deceased

plaintiff instructed his grandson PW 5 to withdraw the notice. Accordingly PW 5 prepared two

applications for the withdrawal and presented them to the postal authorities. The notice, Ex. A

meant for the first respondent and Ex. E meant for the original second defendant were withheld

by the postal authorities. These notices were produced in court by the postal authorities during the

hearing of the case. In our opinion, the evidence of PW 5 must be accepted as true, because it is

110

corroborated by the circumstance that the two notices, Exs. A and E were intercepted in the post

office and did not reach their destination. This circumstance also indicates that though there was

no formal communication of the notice, Ex. A to the first respondent, he had sufficient knowledge

of the contents of that notice and was fully aware of the clear and unequivocal intention of Savoy

Ranganna to become separate from other members of the joint family.

5. It is now a settled doctrine of Hindu Law that a member of a joint Hindu family can bring

about his separation in status by a definite, unequivocal and unilateral declaration of his intention

to separate himself from the family and enjoy his share in severalty. It is not necessary that there

should be an agreement between all the coparceners for the disruption of the joint status. It is

immaterial in such a case whether the other coparceners give their assent to the separation or not.

The jural basis of this doctrine has been expounded by the early writers of Hindu Law. The

relevant portion of the commentary of Vijnaneswara states as follows:

[And thus though the mother is having her menstrual courses (has not lost the capacity to

bear children) and the father has attachment and does not desire a partition, yet by the will (or

desire) of the son a partition of the grandfather’s wealth does take place]”

6. Saraswathi Vilasa, placitum 28 states:

[From this it is known that without any speech (or explanation) even by means of a

determination (or resolution) only, partition is effected, just an appointed daughter is

constituted by mere intention without speech.]

7. Viramitrodaya of Mitra Misra (Ch. 11. pl. 23) is to the following effect:

[Here too there is no distinction between a partition during the lifetime of the father or

after his death and partition at the desire of the sons may take place or even by the desire (or

at the will) of a single (coparcener)].

8. VyavaharaMayukhaofNilakantabhattaalso states:

[Even in the absence of any common (joint family) property, severance does indeed

result by the mere declaration ‘I am separate from thee’ because severance is a particular state

(or condition) of the mind and the declaration is merely a manifestation of this mental state

(or condition).]” (Ch. IV, S. iii-I).

Emphasis is laid on the “budhivisesha” (particular state or condition of the mind) as the

decisive factor in producing a severance in status and the declaration is stated to be merely

“abhivyanjika” or manifestation which might vary according to circumstances. In Suraj Narainv.

Iqbal Narain [ILR 35 All 80], the Judicial Committee made the following categorical statement

of the legal position:

“A definite and unambiguous indication by one member of intention to separate

himself and to enjoy his share in severalty may amount to separation. But to have that

effect the intention must be unequivocal and clearly expressed … Suraj Narain alleged

that he separated a few months later; there is, however, no writing in support of his

111

allegation, nothing to show that at that time he gave expression to an unambiguous

intention on his part to cut himself off from the joint undivided family.”

In a later case – Girja Bai v. Sadashiv Dhundiraj [ILR 43 Cal 1031] – the Judicial Committee

examined the relevant texts of Hindu Law and referred to the well-marked distinction that exists

in Hindu law between a severance in status so far as the separating member is concerned and a de

facto division into specific shares of the property held until then jointly, and laid down the law as

follows:

“One is a matter of individual decision, the desire on the part of any one member to

sever himself from the joint family and to enjoy his hitherto undefined or unspecified

share separately from the others without being subject to the obligations which arise from

the joint status; whilst the other is the natural resultant from his decision, the division.

and separation of his share which may be arrived at either by private agreement among

the parties, or on failure of that, by the intervention of the Court. Once the decision has

been unequivocally expressed and clearly intimated to his co-sharers, his right to obtain

and possess the share to which he admittedly has a title is unimpeachable; neither the cosharers can question it nor can the Court examine his conscience to find out whether his

reasons for separation were well-founded or sufficient; the Court has simply to give

effect to his right to have his share allocated separately from the others.”

In Syed Kasamv.Jorawar Singh [ILR 50 Cal 84], Viscount Cave, in delivering the judgment

of the Judicial Committee, observed:

“It is settled law that in the case of a joint Hindu family subject to the law of the

Mitakshara, a severance of estate is effected by an unequivocal declaration on the part of

one of the joint holders of his intention to hold his share separately, even though no

actual division takes place; and the commencement of a suit for partition has been held to

be sufficient to effect a severance in interest even before decree.”

These authorities were quoted with approval by this Court in

AddagadaRaghavammav.AddagadaChenchamma[(1964) 2 SCR 933] and it was held that a

member of a joint Hindu family seeking to separate himself from others will have to make known

his intention to other members of his family from whom he seeks to separate. The correct legal

position therefore is that in a case of a joint Hindu family subject to Mitakshara law, severance of

status is effected by an unequivocal declaration on the part of one of the jointholders of his

intention to hold the share separately. It is, however, necessary that the member of the joint Hindu

family seeking to separate himself must make known his intention to other member of the family

from whom he seeks to separate. The process of communication may, however, vary in the

circumstances of each particular case. It is not necessary that there should be a formal despatch to

or receipt by other members of the family of the communication announcing the intention to

divide on the part of one member of the joint family. The proof of such a despatch or receipt of

the communication is not essential, nor its absence fatal to the severance of the status. It is, of

112

course, necessary that the declaration to be effective should reach the person or persons affected

by some process appropriate to the given situation and circumstances of the particular case.

Applying this principle to the facts found in the present case, we are of opinion that there was a

definite and unequivocal declaration of his intention to separate on the part of Savoy Ranganna

and that intention was conveyed to Respondent 1 and other members of the joint family and

Respondent 1 had full knowledge of the intention of Savoy Ranganna. It follows therefore that

there was a division of status of Savoy Ranganna from the joint Hindu family with effect from

January 8, 1951 which was the date of the notice.

9. It was, however, maintained on behalf of the respondents that on January 10, 1951 Savoy

Ranganna had decided to withdraw the two notices, Exs. A & E and he instructed the postal

authorities not to forward the notices to Respondent 1 and other members of the joint family. It

was contended that there could be no severance of the joint family after Savoy Ranganna had

decided to withdraw the notices. In our opinion, there is no warrant for this argument. As we have

already stated, there was a unilateral declaration of an intention by Savoy Ranganna to divide

from the joint family and there was sufficient communication of this intention to the other

coparceners and therefore in law there was in consequence a disruption or division of the status of

the joint family with effect from January 8, 1951. When once a communication of the intention is

made which has resulted in the severance of the joint family status it was not thereafter open to

Savoy Ranganna to nullify its effect so as to restore the family to its original joint status. If the

intention of Savoy Ranganna had stood alone without giving rise to any legal effect, it could, of

course, be withdrawn by Savoy Ranganna, but having communicated the intention, the divided

status of the Hindu joint family had already come into existence and the legal consequences had

taken effect. It was not, therefore, possible for Savoy Ranganna to get back to the old position by

mere revocation of the intention. It is, of course, possible for the members of the family by a

subsequent agreement to reunite, but the mere withdrawl of the unilateral declaration of the

intention to separate which already had resulted in the division in status cannot amount to an

agreement to reunite. It should also be stated that the question whether there was a subsequent

agreement between the members to reunite is a question of fact to be proved as such. In the

present case, there is no allegation in the written statement nor is there any evidence on the part of

the respondents that there was any such agreement to reunite after January 8, 1951. The view that

we have expressed is borne out by the decision of the Madras High Court in Kurapati

Radhakrishna v.KurapatiSatyanarayana[(1948) 2 MLJ 331], in which there was a suit for

declaration that the sales in respect of certain family properties did not bind the plaintiff and for

partition of his share and possession thereof and the plaint referred to an earlier suit for partition

instituted by the 2nd defendant in the later suit. It was alleged in that suit that “the plaintiff being

unwilling to remain with the defendants has decided to become divided and he has filed this suit

for separation of his one-fifth share in the assets remaining after discharging the family debts

separated and for recovery of possession of the same”. All the defendants in that suit were served

with the summons and on the death of the 1st defendant therein after the settlement of issues, the

113

plaintiff in that action made the following endorsement on the plaint: “As the 1st defendant has

died and as the plaintiff had to manage the family, the plaintiff hereby revokes the intention to

divide expressed in the plaint and agreeing to remain as a joint family member, he withdraws the

suit.” It was held by the Madras High Court that a division in status had already been brought

about by the plaint in the suit and it was not open to the plaintiff to revoke or withdraw the

unambiguous intention to separate contained in the plaint so as to restore the joint status and as

such the members should be treated as divided members for the purpose of working out their

respective rights.

10. We proceed to consider the next question arising in this appeal whether the plaint filed on

January 13, 1951 was validly executed by Savoy Ranganna and whether he had affixed his thumb

impression thereon after understanding its contents. The case of the appellants is that Sri M.S.

Ranganathan prepared the plaint and had gone to the Sharda Nursing Home at about 9.30 or 10

a.m. on January 13, 1951. Sri Ranganathan wrote out the plaint which was in English and

translated it to Savoy Ranganna who approved the same. PW 2, the clerk of Sri Ranganathan has

deposed to this effect. He took the ink-pad and affixed the left thumb impression of Savoy

Ranganna on the plaint and also on the vakalatnama. There is the attestation of Sri M.S.

Ranganathan on the plaint and on the vakalatnama. The papers were handed over to PW 2 who

after purchasing the necessary court-fee stamps filed the plaint and the vakalatnama in the court

at about 11.30 a.m. or 12 noon on the same day. The evidence of PW 2 is corroborated by PW 5

Chinnanna. Counsel on behalf of the respondents, however, criticised the evidence of PW 2 on

the ground that the doctor, DW 6 had said that the mental condition of the patient was bad and he

was not able to understand things when he examined him on the morning of January 13, 1951.

DW 6 deposed that he examined Savoy Ranganna during his usual rounds on January 13, 1951

between 8 and 9 a.m. and found “his pulse imperceptible and the sounds of the heart feeble”. On

the question as to whether Savoy Ranganna was sufficiently conscious to execute the plaint and

the Vakalatnama, the trial court has accepted the evidence of PW 2, Keshavaiah in preference to

that of DW 6. We see no reason for differing from the estimate of the trial court with regard to the

evidence of PW 2. The trial court has pointed out that it is difficult to accept the evidence of D.W

6 that Savoy Ranganna was not conscious on the morning of January 13, 1951. In crossexamination DW 6 admitted that on the night of January 12, 1951 Savoy Ranganna was

conscious. He further admitted that on January 13, 1951 he prescribed the same medicines to

Savoy Ranganna as he had prescribed on January 12, 1951. There is no note of the necessary data

in the case sheet, Ex. 1 to suggest that Savoy Ranganna was not conscious on January 13, 1951. It

is therefore not unreasonable to assume that the condition of Savoy Ranganna was the same on

January 13, 1951 as on January 12, 1951 and there was no perceptible change noticeable in his

condition between the two dates. In these circumstances it is not possible to accept the evidence

of DW 6 that Savoy Ranganna was unconscious on the morning of January 13, 1951. It was

pointed out on behalf of the respondents that DW 7, Miss Arnold has also given evidence that the

condition of Savoy Ranganna became worse day by day and on the last day his condition was

114

very bad and he could not understand much, nor could he respond to her calls. The trial court was

not impressed with the evidence of this witness. In our opinion, her evidence suffers from the

same infirmity as of DW 6, because the case sheet, Ex. 1 does not corroborate her evidence. It is

also difficult to believe that DW 7 could remember the details of Savoy Rangannacase after a

lapse of three years without the help of any written case sheet. There is also an important

discrepancy in the evidence of DW 7. She said that on January 13, 1951 she called DW 6 at 12

noon since the condition of the patient was very bad, but DW 6 has said that he did not visit

Savoy Ranganna after 8 or 9 a.m. on that date. Comment was made by Counsel on behalf of the

respondents that Sri Ranganathan was not examined as a witness to prove that he had prepared

the plaint and Savoy Ranganna had affixed his thumb impression in his presence. In our opinion,

the omission of Sri Ranganathan to give evidence in this case is unfortunate. It would have been

proper conduct on his part if he had returned the brief of the appellants and given evidence in the

case as to the execution of the plaint and the vakalatnama. But in spite of this circumstance we

consider that the evidence of the appellants on this aspect of the case must be accepted as true. It

is necessary to notice that the plaint and the vakalatnama are both counter-signed by Sri

Ranganathan a responsible advocate and it is not likely that he would subscribe his signatures to

these documents if they had been executed by a person who was unable to understand the

contents thereof. As we have already said, it is unfortunate that the Advocate Sri Ranganathan has

not been examined as a witness, but in spite of this omission we are satisfied that the evidence

adduced in the case has established that Savoy Ranganna validly executed the plaint and the

vakalatnama and that he was conscious and was in full possession of his mental faculties at the

time of the execution of these two documents. It follows therefore that the appellants and

Respondent 4 who are the daughters and legal representatives of Savoy Ranganna are entitled to a

decree in the terms granted by the District Judge of Mysore.

11. For the reasons expressed, we hold that this appeal should be allowed, the judgment of the

Mysore High Court dated December 5, 1960 in R.A. No. 81 of 1956 should be set aside and that

of the District Judge, Mysore dated October 31, 1955 in OS No. 34 of 1950-51 should be

restored. The appeal is accordingly allowed with costs.