| Introduction | jurisprudence |

| sections | section 10, 11 |

| relevant Case laws | rosher vs rosher Muhammad Raza vs Abbas Bandi Zoroastrian cooperative housing society vs district registrar Talk vs Moxhay |

| present problem | question related |

| conclusion | decision as per our reasoning |

Alienation under TPA means that transfer of property to transferee by transferor either by sale, or mortgage, or exchange,etc. When condition is put on the transfer of property, said to be condition restraining alienation. The significance of condition restraining alienation lies in striking a balance between individual property rights and societal interests, preventing unfair restrictions while allowing reasonable conditions.

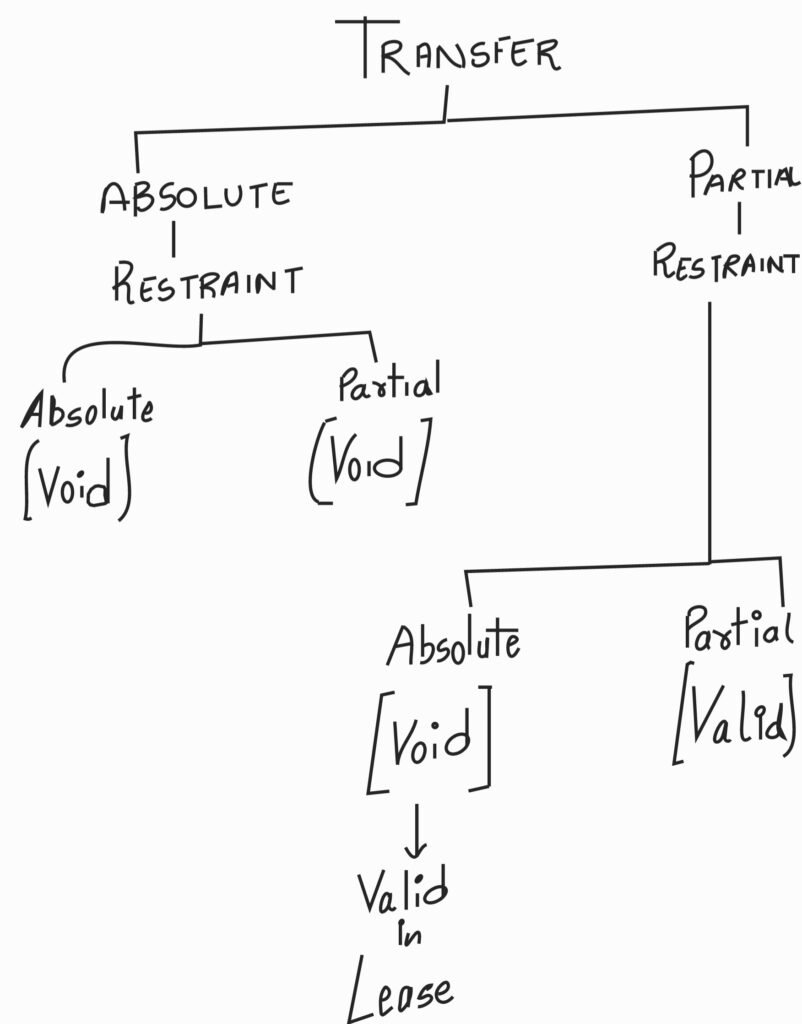

Section 10 states that if the person receiving the property is entirely prohibited from transferring it to someone else due to a condition set at the time of the transfer, that condition becomes void. However, the original transfer from the giver to the receiver remains valid.

Condition is of two types:

- Condition Precedent (sec 26 tpa)

- Condition Subsequent (Section 29 tpa)

Condition Precedent

It is given in Section 26 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. Any condition that is required to be fulfilled before the transfer of any property is called a condition precedent. This condition is not to be strictly followed and the transfer can take place even when there has been substantial compliance of the condition. For example, A is ready to transfer his property to B on the condition that he needs to take the consent of X, Y and Z before marrying. Z dies and afterward, B takes the consent of X and Y so the transfer can take place as there has been substantial compliance.

Condition Subsequent

It is given in Section 29 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882. Any condition that is required to be fulfilled after the transfer of any property is called condition subsequent. This condition is to be strictly complied with and the transfer will happen only after the completion of such condition. For example, A transfers any property ‘X’ to B on the condition that he has to score above 75 percent in his university exams. If B fails to achieve 75 percent marks then the transfer will break down and the property will revert back to A.

Section 10 of TPA:

Condition restraining alienation.—Where property is transferred subject to a condition or limitation absolutely restraining the transferee or any person claiming under him from parting with or disposing of his interest in the property, the condition or limitation is void, except in the case of a lease where the condition is for the benefit of the lessor or those claiming under him: provided that property may be transferred to or for the benefit of a women (not being a Hindu, Muhammadan or Buddhist), so that she shall not have power during her marriage to transfer or charge the same or her beneficial interest therein.

In simple words, it means that when a property is transferred to transferee and transferor puts condition on such property absolutely, then that condition is void but the transfer is valid. But this rule does not apply when condition is partial.

So, there are two types of Restraint, i.e., Absolute and Partial: Absolute means the restrictions as a whole on property. Whereas Partial is restriction not as whole, but there are some restrictions on property.

An absolute restraint on alienation occurs when it entirely removes or limits the right to dispose of property. This section protects the transferee of immovable property from absolute restraints on dealing with the property as its owner. A sells his house to B with a condition that B cannot transfer the house to anyone except C. This condition is void because C may never choose to purchase the property.

Partial restraint: where the restraint doesn’t substantially take away the power of alienation but only limits it to some extent, it is considered a partial restraint and such restraints are generally valid and enforceable.Conditions like prohibiting the transferee from transferring the property by gift or restricting the transfer to family members or a particular person are considered partial restraints and are generally valid.

Exceptions to Condition Restraining Alienation

Lease

A lease involves the transfer of a limited interest where the lessor (transferor) retains ownership and conveys only the right of enjoyment to the lessee (transferee). The lessor can impose a condition prohibiting the lessee from assigning their interest or subleasing the property to another person. Despite being a restraint on the lessee against alienation, such a condition is considered valid and the lessee cannot transfer their interest without the lessor’s consent.

Married Women

When property is transferred to a married woman who is not a Hindu, Muslim or Buddhist, the transferor can impose a condition restraining alienation and such a condition will not be void under Section 10.Therefore, a property may be transferred to a married non-Hindu woman for her life with a condition that she cannot transfer it.

Section 11 TPA:

Restriction repugnant to interest created.—

Where, on a transfer of property, an interest therein is created absolutely in favour of any person, but the terms of the transfer direct that such interest shall be applied or enjoyed by him in a particular manner, he shall be entitled to receive and dispose of such interest as if there were no such direction.

Where any such direction has been made in respect of one piece of immoveable property for the purpose of securing the beneficial enjoyment of another piece of such property, nothing in this section shall be deemed to affect any right which the transferor may have to enforce such direction or any remedy which he may have in respect of a breach thereof.

This section deals with where a property is transferred to transferee, but transferor puts restrictions on interest created on the property, is termed as void. But it has an exception

If the transferor possesses another piece of immovable property, they can impose conditions or restrictions on the transferee’s right of enjoyment for the benefit of that property. For example, if A sells two properties, X and Y, to B with the condition that a portion of X adjoining Y must be kept open for the benefit of Y, this condition would be considered valid.

Relevant Case laws:

Rosher vs Rosher

facts:

A person J B Rosher died leaving behind his wife and a son . He left his entire property to Son, under his Will. The Will also provided that if Son wanted to sell the property, or if any of his heirs wanted to do so, they must offer it to Widow first at 3600£ and she would have an option to purchase it at one- fifth of the value of the same, as it was assessed at the time of the testator’s death. The Will further provided that if the son or any of his heirs wanted to let this manor on rent, they could do so freely only for a period of three years. If the tenancy exceeded the three years time period, Widow would have the option to occupy the premises, for the period in excess of three years, at a fixed rent. The rent was fixed as 25 for the whole year. The son or his heirs were under an obligation therefore to offer the premises to W first, and only when she declined to take it, could they let it out to other persons.Widow filed a suit against her son.

issue:

What was the nature of the conditions incorporated under the Will; and whether itconstituted an absolute or partial restraint on the power of alienation of this property?

judgement:

The character of restraint was:→ First, if Son wanted to sell the property, he had to first offer it to Widow, a person specifically named under the Will.→ Second type of restraint was with respect to money or price, as it was provided in the Will, that Widow could purchase the property at a specific price, i.e., 3600, irrespective of whatever might have been its market value.→ Third, the beneficiaries, under the Will, were not free to even give it on lease, as a lease for above the time period of three years, could again entitle Widow to take the property at a very small rent, at her option.The court held that these restrictions amounted to an absolute restraint on Son’s and his heir’s power of alienation and were therefore void.They were entitled to ignore them, as if these conditions did not exist on paper, and could sell it or let it out to anyone for any time period, without any cause of action arising in favour of Widow.The court said, ‘to compel the son, if he chose to sell, at one fifth of the value of the estate, is really a prohibition of alienation during the widow’s life time’.Any restriction which substantially takes away the power of alienation, is void as being repugnant to the very conception of ownership. A partial restraint which does not deprive the owner of his power of alienation, is valid.

It was concluded that any condition which restraints further transfer absolutely, is null and void.

Muhammad Raza vs Abbas Banci Bibi

facts:

A person A married with two wives W1 & W2. According to an agreement in their capacity as wives, from this very time be declared permanent owners of the property. With a condition that the said females shall not have power to transfer this property to a stranger; but the ownership thereof as family property shall devolve on the legal heirs of both the above-named wives, from generation to generation. After the death of A and W1, W2 had sold or mortgaged it all before her death, which occurred on July, 26 1914. Her transferees remained in undisturbed possession for nearly twelve years after her death. In March 1926, the suit out of which this appeal has arisen was instituted by the respondent in the Court of the Subordinate Judge of Fyzabad for the recovery of two-thirds of W2 share from the appellants, in whose possession the properties had come under the alienations above referred to. Respondent is one of the heirs of the W2.

issue:

Was the restriction placed by the agreement deed, upon W2’s power of alienation valid and legally enforceable?

judgement:

On the assumption that W2 took under the terms of the document in question an absolute estate subject only to this restriction, their Lordships think that the restriction was not absolute but partial; it forbids only alienation to strangers, leaving her free to make any transfer she pleases within the ambit of the family.A condition that W2 would not alienate the property outside the family it was held that the restraint was only partial and such a partial restraint was neither repugnant to law nor to justice, equity and good conscience.A condition to sell only to specific persons is void, but a condition not to sell outside the family would be a partial restraint.Concerned the provisions of Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act which recognizes the validity of a partial restriction upon a power of disposition in the case of a transfer inter vivos.

In their Lordships’ opinion W2 had no power to transfer any part of the properties to the appellants, and upon her death the respondent became entitled to the two-thirds share in the properties which she claims.

Zoroastrian cooperative housing society vs District Registrar

facts:

A society was registered under the Bombay Co-operative Societies Act, with the object of constructing houses for residential purposes, and according to the byelaws, the membership was restricted only to Parsis. The byelaws also contained a condition that no member could alienate the house to non-Parsis. The High Court of Bombay stated that a restriction based on religion, race or caste contained in a byelaw on the member’s right in a cooperative housing society to transfer his membership coupled with his right to alienate his interest in the immovable property would be bad in the eyes of law. Restriction on the member’s right to transfer membership and/or his interest in the property, to a non-Parsi was held violative of s. 10, and is therefore void. The matter went to the Supreme Court in appeal.

Appellant contended thatThere was nothing in the Act or the Rules which precluded a society from restricting its membership to persons of a particular persuasion, belief or tenet and the High Court was in error in holding membership could not be restricted to these members. As bye-law, was perfectly valid There was nothing illegal in certain persons coming together to form a society or to restrict membership in it or to exclude the general public at its discretion with a view to carry on its objects smoothly. There was no absolute restraint on alienation to attract Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act and there was only a partial restraint, if any, that was valid in law. Respondent contention no bye-law could be recognized which was opposed to public policy or which was in contravention of public policy in the context of the Constitution of India and the rights of an individual under the laws of the country. Counsel also contended that the High Court was right in holding that the concerned bye-law operated as a restraint on alienation and such a restraint was clearly invalid in terms of Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act.

issue:

Whether the Restriction on the member’s right to transfer membership and/or his interest in the property, to a non-Parsi violative of s. 10 of the Transfer of Property act?

judgement:

The Apex Court allowed the appeal and held that when a person accepts the membership of a co-operative society by submitting himself to its byelaws and places on himself a qualified restriction on his right to transfer property by stipulating that same would be transferred with prior consent of society to a person qualified to be a member of the society, it could not be held to be an absolute restraint on alienation offending s. 10 of the TP Act.Hence, it set aside the finding of the High Court that the restriction placed on rights of members of a society not to sell the property allotted, to non-Parsis was an absolute restraint on alienation as unsustainable.

The Supreme Court held that this clause in the byelaws that a person could sell it only to Parsis and not to a non-Parsi was a partial restraint and not an absolute one.

Tulk vs Moxhay

facts:

The claimant, Tulk, owned several properties in Leicester Square, London, and sold one such property to another, making the purchaser promise to not build on the property so as to help keep Leicester Square ‘uncovered with buildings’ and creating an equitable covenant. The purchaser subsequently sold the land and it underwent multiple transactions, and was eventually purchased by the defendant, Moxhay. Whilst Moxhay was aware of the covenant attached to the land at the time of the transaction, he claimed it was unenforceable as he had not been a party to the original transaction in which the covenant had been made.

issue:

Whether the covenant that does not run with the land can be enforced?

Whether a party shall be permitted to use the land in a manner inconsistent with the contract entered into by his seller with notice of which he purchased?

judgment:

For the beneficial enjoyment of his own immovable property, a third person has the right independently of any interest in the immovable property of another to direct the enjoyment in a particular manner of the latter’s property, such right or obligation may be enforced against a transferee with notice thereof or a gratuitous transferee of the property affected thereby. But not against a transferee for consideration and without notice of the right or obligation nor against such property in his hands. In equity, a negative covenant or agreement restricting the user of the land as aforesaid, attaches itself to the land and runs with it. It is binding on the purchaser who has notice of the covenant. Such covenant should be negative and this rule does not apply in case of positive or affirmative covenant. The transferor may impose conditions restraining the enjoyment of land if such restrictions are for the benefit of adjoining land of the transferor. The court noted that the price would be affected by the covenant but then nothing would be more inequitable than that the original purchaser should be able to sell the property the next day for a greater price, in consideration of the assignee being allowed to escape from the liability which he had himself undertaken.

The court held that no one purchasing with notice of an equity can stand in a different situation from that of the party from whom he purchased; and therefore X, who was aware of the conditions in the contract, irrespective of their character, was bound by it.

(a) ‘A’ sells a plot of land to ^ prime B’ for consideration. In the transfer deed, prime A’ puts a condition that B’ would not sell it to anyone. ‘B’ agrees to abide by this condition. After the title passes and property vests in ‘B’, ‘B’ sells it to ‘C’. A’ files a suit claiming possession of the property, on the ground that B’ has committed breach of condition of contract. Decide whether such condition is valid as per legal provisions and decided cases. (b) X’ sells his agricultural land to ‘Y’ with a condition that ‘Y’ can cultivate only wheat but cannot grow the crops of paddy.

Answer: (a) the condition put by A on B is void as it is absolutely restraining. (b) this condition is absolute and void.

Discuss giving reasons the validity of conditions imposed in the following transfers: (a) Sale of a house with the conditions that purchaser has to use the house. For residential purpose & will not part with the possession of the said house in favour of any other person. (b) Sale of a house with the condition that purchaser will never construct on it a house obstructing the view of another house of the seller. (c) An absolute gift of a house with a direction that the donee shall reside in it. (d) A gift of a house with a condition that if the donee does not reside in it, the gift will be forfeited.

Answer: (a) the condition is absolutely restraining and void. (b) this condition is partial and valid. (c) the condition is partial and valid. (d) the condition is absolutely restraining and void.