A Legal right can be said as, “that power which a man has to make a person or persons do or refrain from doing a certain act or certain acts, so far as the power arises from society imposing a legal duty upon a person or persons.” According to Salmond: “A right is an interest recognized and protected by a rule of right. It is any interest respect for which is a duty, and the disregard of which is a wrong.” The words commonly used to describe legal relations frequently convey multiple inconsistent meanings. The confusion that results from this inherent weakness in the language of the law has produced many attempts to reduce that language to terms that suggest a single idea

Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld was a professor at Stanford University and later Yale University who wrote only a few articles before his premature death in 1918.

His most famous article Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning became a canonical landmark in American jurisprudence.

His work remains a powerful contribution to modern understanding of the nature of rights and the implications of liberty. To reflect Hohfeld’s continuing importance, a chair at Yale University was named after him. 3 Since the appearance of his Fundamental Legal Conceptions in 1913, his work has attracted both followers and critics; his ideas have appeared in United States Supreme Court opinions, and the Restatement of Property.

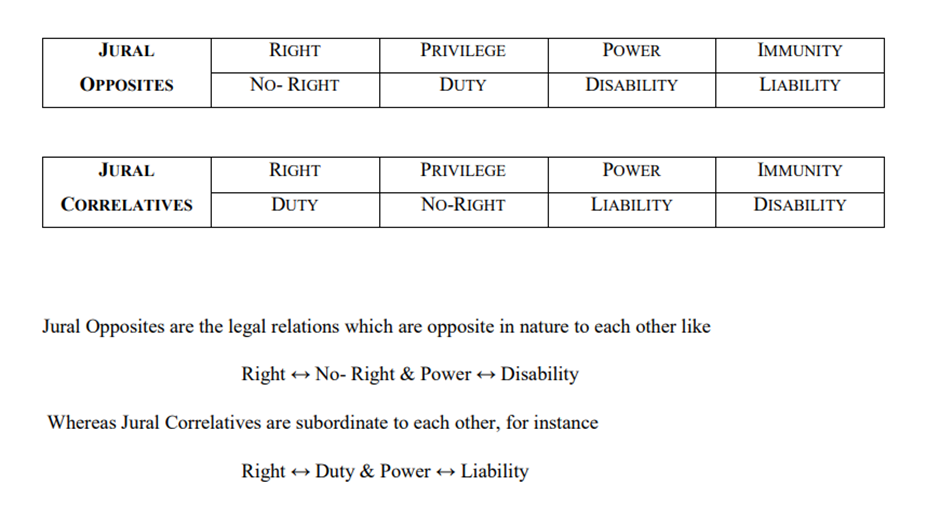

THE HOHFELD’S RELATIONS Hohfeldian analysis enhances legal reasoning by allowing one to deduce one legal concept from another.

Professor Hohfeld identified eight atomic particles by splitting the atom of legal discourage which he called “the lowest common denominators of the law.

He defined these eight basic jural relations to clarify legal thinking and understanding, Hohfeld divided the eight into pairs which cannot exist together (opposites), and those which must exist together (correlatives).

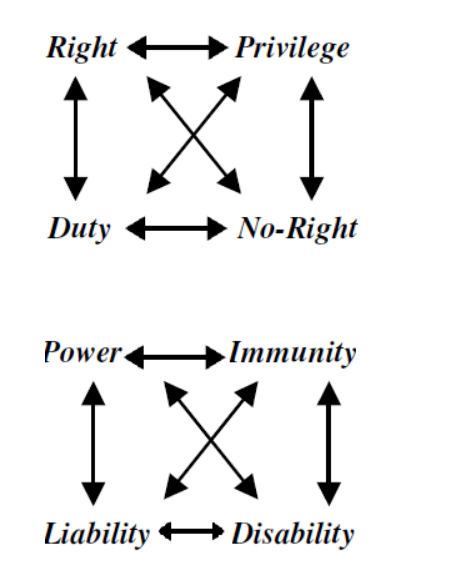

The vertical arrows couple jural correlatives, two legal positions that entail each other, whereas the

diagonal arrows couple jural opposites, two legal positions that deny each other. The Horizontal

arrows couple jural contradictories.

Hohfeld’s relations can be best understood through examples. Following are the different examples of different legal relations. Hohfeld explained the correlations as “if X has a right against Y that he shall stay off the formers (X) land, the correlative is that Y is under a duty toward X to stay off his place”. Thus, a right is enjoyed by an individual as against another individual is that the second shall do or refrain from doing something for the first. Thus X has a right against Y with regard to act A, if and only if Y has a duty to X with regard to act A.

Hohfeld has also explained “no-right” and “privilege” concepts as well. They are, respectively, the opposites of “right” and “duty.” The terms “privilege” and “no-right” are also correlatives. X has a privilege against Y with regard to act A, if and only if Y has a no-right against X with regard to A.

A “liability” is the correlative of a “power”. A person X is under a liability, if there is an act another person can perform that will affect the legal relations of X.

“Disabilities” and “immunities” are the opposites of “powers” and “liabilities”. If X does not have a power with regard to individual Y, then X is under a disability with regard to Y. Similarly, if Y is not under a liability with regard to X, then Y has an immunity with regard to X.

Whereas “Disabilities” and “immunities” are also correlatives of each other. If X has a disability with regard to Y, that is, X has no power to affect Y’s legal relations, then Y is immune from having his or her legal relations affected by X. Similarly, if Y is immune with regard to X, then X is under a disability with regard to Y.

If rights and duties must always be paired, then no-rights and privileges must also always be paired. Thus, an individual has a no-right against another individual with regard to a particular act if and only if that individual does not have a right against the second individual with regard to that act. Similarly, an individual has a privilege against a second individual with regard to a particular act if and only if the individual does not have a duty toward the second individual with regard to that act.

SOURCES OF HOHFELD’S TERMS Hohfeld explicitly declines to provide any specific definitions for his eight conceptions. They are sui generis. Instead, he accords meaning to these conceptions by articulating their relations, by demonstrating their instantiation in case law and legal scholarship, and by showing how they can be used to reveal sloppy thinking and faulty analyses.

Before understanding further about the Hohfeld’s relations let us first understand what he meant by the terms “right”, “duty”, “privilege”, “immunity”. The first thing that needs clarifying is what kind of rights, duties, etc., Hohfeld was talking about and where do they come from? Hohfeld’s rights, duties, privileges, and no-rights are simply shorthand terms for saying what liabilities the law prescribes between two people for the doing or not doing of an act.

Hohfeld’s “duty” arises from rules of positive law.

The term “DUTY” is commonly misinterpreted by others as Hohfeld used it. By “duty” he did not mean the moralist duties or duties of a son towards his father; Hohfeld was talking about legal duties, whereas powers, immunities, liabilities and disabilities involve changes in legal relations they exist in situations in which the potential change in legal relations is dependent on the volitional act of some person.

A “RIGHT” as Hohfeld viewed it, is merely a “duty” from the other fellow’s viewpoint. Rights and Duties, Hohfeld said, are jural correlatives. Whenever there is a duty there must also be a correlative right, and vice versa.

Hohfeld’s system is often misunderstood, and probably the most frequently misunderstood of his terms is his “PRIVILEGE.” To many people when someone has a “privilege” it means that he is free to act or not as he sees fit. Thus, one of Hohfeld’s critics wrote: [F]or me to have a privilege of doing a thing, means . . . (1) to have no duty of doing the thing, (2) to have no claim or right against others that they should refrain from interfering with my doing the thing, and (3) to be under no duty not to do the thing.

For example, under ordinary circumstances A owes B neither a duty to paint A’s house nor a duty not to paint it. That is to say, A is ordinarily privileged as against B to paint A’s house or not as he sees fit. In neither case would the rules of law make him liable to B. However, suppose A enters into a binding contract with B whereby A agrees to paint the house. Under these circumstances A would owe B a duty to paint the house since the law would make him liable to B (in contract) if he failed to paint it as he promised. A would not have a privilege as against B not to paint the house, but he would have a privilege to paint the house. On the other hand, if A contracts with B not to paint the house, then he would have no privilege to paint the house, but he would be privileged not to paint it. These illustrations show that it is possible, under appropriate circumstances, for A to have both privileges (to do the thing or not to do it), or to have just one of them (either one). Evidently it is not possible for A to have neither privilege, for that would mean A would be liable to B whether he painted the house or not.

“POWER” is one’s ability to alter legal (or moral) relations.

For example, when someone make an offer of a contract, that gives the offeree the power to create a contract by accepting the offer (or not). If the power to create the contract is exercised, then both parties have rights and duties with respect to each other. Courts have power, only if plaintiffs or prosecutors exercise their power to commence a lawsuit.

“IMMUNITY”: If X has an immunity against Y, it means that Y has no power to change X’s legal position with respect to any entitlements covered by the immunity. For instance, if the state has no power to place me under a duty to wear a hat when I go out, I have immunity in that respect, and the state a disability (a correlative to immunity). Simmonds in notes of ‘Constitutional Bills of Rights’ stated that: “Hohfeldian analysis of rights is very important given its clarity and precision to ensure that the state does not overpower the individual. Hohfeld’s analysis is useful in getting a clear sight of the jural relations of the parties involved and their legal positions”.

HOHFELD’S CUBE THEORY The theory presented here is that the eight jural relations may be effectively graphed as the eight corners of a cube, and this image unifies all eight into a single logical structure. This structure symbolizes real legal relationships and assists an understanding of the way legal relations work.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE CUBE First arbitrarily choose a place to locate the relation “Right,” and then subsequently locating the other concepts. Here “Right” is placed at the upper left-hand corner of the back of the cube, “Duty” then appears on the corresponding corner of the front of the cube. The next jural relation, “Privilege” which is the opposite of “Duty”, and bears no direct relation to “Right”. So “Privilege” will lie on a diagonal on the same side of the cube as “Duty”, which is the traditional method of symbolizing two opposing statements on a square of opposition. “No-Right” is the correlative of “Privilege”, and thus it appears on the corresponding back corner of the cube. The cube now contains the first four concepts of Hohfeld.

Similarly other jural relations are also place at the corners of the cube as shown in the figure. The cube demonstrates that Hohfeld’s ideas fulfill his original intention – to clarify legal thinking.

Once it is known that there are eight and only eight jural relations, that there are well-defined relationships among them, and that these relationships behave in predictable ways, then the analysis of all legal questions, even the most complex, becomes easier. Two disputing parties are able to define their unsettled question more precisely, and the court, agency, or legislature is able to settle the same question with correspondingly greater precision. Of greater practical interest, however, is the possibility that Hohfeld’s Cube may enable a computer to draw analogies.25