| Introduction | jurisprudence |

| Relevant Case laws | Anglo- Norwegian Fisheries case (United Kingdomvs Norway) Corfu Channel case North sea Continental shelf case |

| present problem | questions related |

| conclusion | decision as per our reasoning |

The Law of Sea is a collection of international treaties and agreements that regulates all marine and maritime activities. It encourages a peaceful relationship between the sea and the coastal states. As one of the main topics of international law, it conducts all maritime economic activities, maintains navigation rules and protects the sea from ruling powers. It regulates the geographical activities of various coastal states and plays a role in conserving the aquatic environment. The Law of the Sea is associated with the convention on the Law of Sea, which is an UN-based international treaty. It was signed in 1982 by 117 states, and was adopted in 1994.

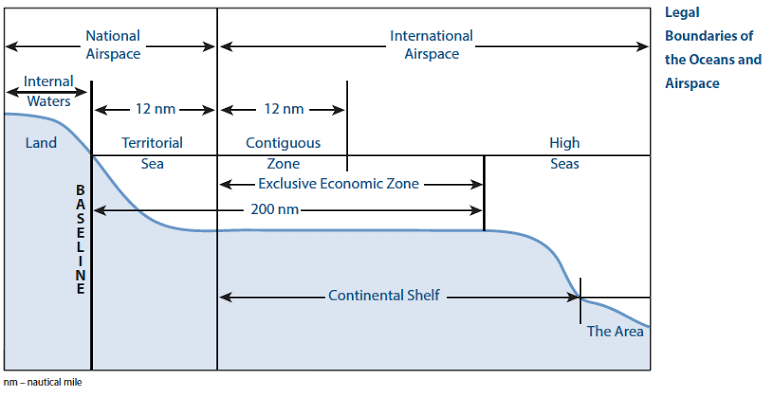

The Law of Sea in international law is the only international convention that stipulates a framework of states in the maritime zones. According to the sea law, marine areas are divided into five zones.The zones are internal waters, contiguous zone, territorial sea, High Seas and the exclusive economic zone.

Baseline

It is the lowest waterline, mostly recognised by the coastal states. It is the line alongside the coastal region along with the seaward limits.

Internal Waters

Internal waters are all the waters that fall landward of the baseline, such as

lakes, rivers, and tidewaters. States have the same sovereign jurisdiction over

internal waters as they do over other territory. There is no right of innocent

passage through internal waters.

Territorial Sea

Everything from the baseline to a limit not exceeding twelve miles is considered the State’s territorial sea. Territorial seas are the most straightforward zone. Much like internal waters, coastal States have sovereignty and jurisdiction over the territorial sea. These rights extend not only on the surface but also to the seabed and subsoil, as well as

vertically to airspace.

While territorial seas are subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the coastal States, the coastal States’ rights are limited by the passage rights of other States, including innocent passage through the territorial sea and transit passage through international straits. This is the primary distinction between internal waters and territorial seas.

There is no right of innocent passage for aircraft flying through the airspace above the coastal state’s territorial sea.

Contiguous Zone

States may also establish a contiguous zone from the outer edge of the territorial seas to a maximum of 24 nautical miles from the baseline. This zone exists tobolster a State’s law enforcement capacity and prevent criminals from fleeing the territorial sea. Within the contiguous zone, a State has the right to both prevent and punish infringement of fiscal, immigration, sanitary, and customs laws within its territory and territorial sea. Unlike the territorial sea, the

contiguous zone only gives jurisdiction to a State on the ocean’s surface and floor. It does not provide air and space rights.

Exclusive Economic Zones

It extends 200 nautical miles to the sea from the baseline. With EEZ, any coastal region has the right to explore, conserve and manage natural sources in the seabed and subsoil, no matter if the resources are living or nonliving. They have exclusive rights to bear every activity like energy production from the sea, water current, and winds. EEZ exclusively allows the rights mentioned above. This zone does not provide the coastal state with the liberty to prohibit navigation (only under various exceptional cases).

High Seas

The ocean surface and the water column beyond the EEZ are referred to as the high seas.These are the ocean’s surface and water column that does not come under the exclusive economic zone, territorial sea, or the internal water. It is called the “Common Heritage Of All Mankind” and is beyond the nation’s jurisdiction. Coastal countries can conduct various activities in the High Seas only if they are peaceful activities like undersea exploration or marine studies.

Continental Shelf

The continental shelf is a natural seaward extension of a land boundary. This seaward extension is geologically formed as the seabed slopes away from the coast, typically consisting of a gradual slope (the continental shelf proper), followed by a steep slope (the continental slope), and then a more gradual slope leading to the deep seabed floor. These three areas, collectively known as the continental margin, are rich in natural resources, including oil, natural gas and certain minerals. The UNCLOS allows a State to conduct economic activities for a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baseline, or the continental margin where it extends beyond 200 nautical miles.

The concept of continental shelf is mainly co-related with an exploitation of the natural resources from the sea adjacent to theterritorial sea. This was one of the important developments after the Second World War in relation to the law of sea was the evolution and acceptance of the concept of the continental shelf. The President of the United States proclaimed that the natural resources of the continental shelf were ‘beneath the high seas but contiguous to the coasts of the United States as appertaining to the United States and subject to its jurisdiction and control’ The continental shelf was regarded ‘as an extension of the landmassof the coastal nation’.

Rights of Coastal State over Continental Shelf under UN Conventionon the Law of the Sea, 1982

Article 7 of the Convention provides various provisions withregard to the rights of coastal states. The coastal State enjoys limitedsovereign rights over the continental shelf for the purpose of exploringand exploiting its ‘natural resources’, and not sovereignty. These rightsare exclusive in the sense that no one can undertake these activitieswithout the express consent of the coastal State or make a claim to thecontinental shelf. They also do not depend on occupation, effective ornotional, or any express proclamation.The ‘natural resources’ of the continental shelf consist of mineraland other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil, together withliving organisms which at the harvestable stage, either are immobile onor under the seabed or are unable to move except in constant physicalcontract with the seabed or subsoil.

Rights of Other States in Continental Shelf under UN Convention onthe Law of the Sea, 1982

The Convention also gives various rights to the Other States. The rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf do not affect the legal status of the superjacent waters or of the airspace above those waters. The exercise of the rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf must not infringe or result in any unjustifiable inference with navigation and other rights and freedoms of other states as provided for this convention( art. 78 ). Also all states are entitled to lay submarine cables and pipelines on continental shelf(art. 79).

Relevant Case Laws:

Corfu Channel CaseICJ Reports 1949, p.4

North Sea Continental Shelf Cases ICJ Reports, 1969, p.3

Anglo – Norwegian Fisheries Case (UK vs Norway)

facts:

The coastline of Norway was deeply indented by fjords and sunds (sound) and was fronted by a fringe of islands and rocks (the skjaergaard) which was close to mainland. Norway measured its territorial sea not from the low-water mark but from the straight baselines linking the outermost points of land along it. United Kingdom challenged the legality of Norway’s straight baseline system as Norway enclosed waters within its territorial sea that would have been high seas.

issue:

Whether or not by reference to the principles of international law applicable in defining baselines, the Norwegian govt was entitled to delimit fisheries zone and exclusively reserve it to nationals?

judgement:

The Court concluded that the method of straight lines, established in the Norwegian system, was imposed by the peculiar geography of the Norwegian coast; that even before the dispute arose, this method had been consolidated by a constant and sufficiently long practice, in the face of which the attitude of Governments bears witness to the facts that they did not consider it to be contrary to international law.

The Court considered that historical data produced lend some weight to the idea of the survival of traditional rights reserved to the inhabitants of the Kingdom over fishing grounds included in the 1935 delimitation.

Such rights, founded on the vital needs of the population and attested by ancient and peaceful uses, may legitimately be taken into account in drawing a line which, moreover, appears to the Court to have been kept within the bounds of what is moderate and reasonable.

Although the Court upheld the validity of straight baselines in international law, it made clear that the coastal State does not have an unfettered discretion as to how it draws straight baselines, and it laid down a number of conditions governing the drawing of such baselines. 1. First, such lines must be drawn so that they do “not depart to any appreciable extent from the general direction of the coast”. 2. Secondly, they must be drawn so that the “sea areas lying within these lines are sufficiently closely linked to the land domain to be subject to the regime of internal waters”. 3. Thirdly, the Court stated that it is legitimate to take into account “certain economic interests peculiar to a region, the reality and importance of which are clearly evidenced by a long usage”.

The Court finally held that the method employed by Norway to delimit its territorial waters was not contrary to international law. The principle of straight baseline was subsequently adopted in Geneva Convention on Territorial Waters and Contiguous Zone of 1958 and U.N. Convention on Law of the Sea, 1982.